Why Jobs Take Your Soul And How Conservatives Can Fix Them

Most conservatives embrace the “work hard, pray hard” mentality that is typical of people who are looking for a reason to prove that they are good and worthy, which raises the question of why conservatives have such a whipped, domesticated mentality. Undoubtedly, being a minority viewpoint in a world that is gradually grinding toward the Left and has been for centuries induces such despondency.

However, this confuses a method for the goal, which is an eternal failing. Our purpose is to conserve the best of our civilization, not the best option offered by the current regime or political order. This is why the notion of “American conservatives” proves ridiculous; there is no conservatism specific to a political entity, because incarnations of civilization serve the root civilization itself, which in our case is Western Civilization.

If we are to conserve the best of our civilization independent of the current year, we require an understanding not just of philosophy and prescriptive methods, but what provides a healthy life for the citizens who will create that civilization in each new generation. This raises the question of whether “work,” or jobs and the bureaucracy required to run an independent business, are healthy for those citizens. For some, these activities do not prove a burden, but these do not appear to be those with an interest in nurturing civilization.

Michel Houellebecq estimates that 90% of the activity in a modern job is not necessary. This makes sense when we consider that with high mobility to citizens, both in socioeconomic status and geographic area, the prime consideration for management regarding any employee role becomes how to replace those employees when they move on. Any role which cannot be replicated presents a problem for management, since then a department must be restructured. Instead, the bureaucracy demands that jobs be subdivided into nearly microscopic roles in telescoping hierarchies which function by “accountability,” or delivery of pre-defined results and conformity to paperwork and attendance demands, rather than a measurement of results, and this even extends into the tax, licensing, certification and regulatory systems that impose their requirements on independent businesses.

All of those influences manifest in make-work, or activities done so that they can be visually noticed whether in the office or on paperwork, so that the managers above the people in question can demonstrate their accountability to those above them. This eventuates in jobs consisting of pro forma activities for the sake of the management hierarchy, which itself suffers from the instability of the accountability system in layers above it:

Back in the early-1930s, renowned economist, John Maynard Keynes, predicted that technical innovations and rising productivity would mean that advanced country workers would be able to work only 15 hours and still enjoy rising living standards.

In a highly amusing, but also somewhat depressing article in Strike! Magazine, David Graeber asks why Keynes’ prophecy has not come true and instead we find ourselves working a range of meaningless “bullshit jobs” that many of us hate:

There’s every reason to believe he [Keynes] was right. In technological terms, we are quite capable of this. And yet it didn’t happen. Instead, technology has been marshaled, if anything, to figure out ways to make us all work more. In order to achieve this, jobs have had to be created that are, effectively, pointless. Huge swathes of people, in Europe and North America in particular, spend their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed. The moral and spiritual damage that comes from this situation is profound. It is a scar across our collective soul. Yet virtually no one talks about it.

…But rather than allowing a massive reduction of working hours to free the world’s population to pursue their own projects, pleasures, visions, and ideas, we have seen the ballooning not even so much of the “service” sector as of the administrative sector, up to and including the creation of whole new industries like financial services or telemarketing, or the unprecedented expansion of sectors like corporate law, academic and health administration, human resources, and public relations…

…It’s important to recognized this deep-rooted difference in values, even in a society that led the Industrial Revolution, and how America has (remarkably) managed to impose some of its workaholism on much of the rest of the world. Here, for instance, is Wikipedia on de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America:

…This rapidly democratizing society, as Tocqueville understood it, had a population devoted to “middling” values which wanted to amass, through hard work, vast fortunes. In Tocqueville’s mind, this explained why America was so different from Europe. In Europe, he claimed, nobody cared about making money. The lower classes had no hope of gaining more than minimal wealth, while the upper classes found it crass, vulgar, and unbecoming of their sort to care about something as unseemly as money; many were virtually guaranteed wealth and took it for granted. At the same time in America, workers would see people fashioned in exquisite attire and merely proclaim that through hard work they too would soon possess the fortune necessary to enjoy such luxuries.

Of the above explanations, only the one offered by de Tocqueville makes sense: in an egalitarian society, being an equal worker is the ideal so that others accept you as not attempting to avoid the burden of equal contribution, and so people make a show of working. When coupled with an accountability culture that measures people by external traits such as completed projects and objectives met, instead of looking at internal traits like intelligence and character, this creates an unbearable urge for everyone to be busy all of the time. This then becomes a form of competition.

You have undoubtedly seen this at an office. A new worker comes in and, instead of leaving at five like everyone else, she stays until six very obviously working on something that looks important. Everyone else in the office realizes that this is the new standard, because the person who stays until six is going to get promoted over the rest and fired last, so soon everyone stays until six. Then someone starts staying until seven…

Since we look at external traits instead of inner ones, we are accumulating people who can do what is asked of them and therefore are kept around despite being abusive:

Research in the United Kingdom and the United States suggests that jerk-infested workplaces are common: a 2000 study by Loraleigh Keashly and Karen Jagatic found that 27 percent of the workers in a representative sample of 700 Michigan residents experienced mistreatment by someone in the workplace. Some occupations, such as medical ones, are especially bad. A 2003 study of 461 nurses found that in the month before it was conducted, 91 percent had experienced verbal abuse, defined as mistreatment that left them feeling attacked, devalued, or humiliated. Physicians were the most frequent abusers.

This abusive work environment creates great stress for the individual, but is joined by the ambiguity of work itself. Jobs separate us by a layer from the effects of our actions; not only are we specialized, so that no one person sees any process from start to finish, but the hierarchy of managers determine success through their own measurements, which are usually pro forma and so do not fully coincide with real-world needs.

Even more, the social requirements of the workplace separate us from actual effectiveness. Managers like people who get along with the team because those people produce fewer complaints, but because this is a formal requirement, sociopaths and antisocial behavior cases recognize it from miles away and are able to fool the managers (a form of “gaming the system”) just about every time. Those who are less likely to think in terms of manipulation are unaware of this requirement, and so come across as more contentious while the actual malefactors slide under the radar.

We can tell this is true because managers rank intelligence last as traits they desire in a worker, well below the conformity surrogates of “professionalism” and “reliability,” because having a worker who causes no problems and is always there makes the manager look good and eliminates risk to his job:

Most people go to work, much as they went to school, for social reasons. They would be lonely otherwise and since most are extroverts, they have no idea what to do with themselves, or how to evaluate what they should be doing, without getting feedback from the group. They gain a sense of uplifting well-being from being part of a happy group, so when others are pleased, they feel contentment. Much of work consists of managing expectations through social interaction, and by pacifying others, achieving the positive estimation of the group.

All of these stages of removal from the actual task serve to benefit the less-competent, punish the competent, and create ambiguity about what will be rewarded. People depend on their paychecks and fear being fired, so they take affirmative steps to ingratiate themselves with others and their managers. This also produces a need for make-work activities. The fundamental uncertainty and unfairness of this situation creates great stress in even the average worker.

We are learning that stress, like inflammation, can be destructive to our health, and jobs induce a unique kind of stress that is a daily event, changing who we are biologically as well as mentally:

Researchers from Brigham Young University (BYU) found that stress could be just as harmful to the human body as a nutritionally poor diet.

The scientists discovered that when female mice were exposed to stress, their gut microbiota — the microorganisms vital to digestive and metabolic health — morphed to look like the mice had been eating a high-fat diet.

“Stress can be harmful in a lot of ways but this research is novel in that it ties stress to female-specific changes in the gut microbiota,” BYU professor of microbiology and molecular biology Laura Bridgewater said in a statement. “We sometimes think of stress as a purely psychological phenomenon but it causes distinct physical changes.”

We can conceive of stress as having several components: it must be a situation we cannot change, which recurs frequently, and which has an impact on our future. Raw production, like owning a farm, produces worry in terms of attempting to achieve results; work induces stress by piling stuff on us to do without certainty of success, especially since that success is divorced from raw production and highly dependent on authority and social influences. Workplaces are stressful because they are necessary and capricious.

Authority tends to work from a negative outlook just as social influences do. These both focus on removing threats more than rewarding good behavior because they are applied from outside the individual by those observing appearances, both of the individual and of the effects in others. This herd behavior effect means that someone who does everything right, but slips up in some crucial way, is destroyed, while those who do most things poorly or in a mediocre way but carefully watch their behavior get ahead. This punishes and removes people with any passion for life, forcing us to hide our inner selves and become actors, not to mention avoid most social interaction because of the risk.

In workplaces, the “heckler’s veto” dominates, meaning that managers focus on eliminating controversy instead of achieving results. This means that if doing something right is not universally accepted, managers select a compromise and therefore consistently dumb-down and make mediocre everything they touch in the interest of avoiding “bad optics.” The external nature of control, based on appearance and not results in reality, guarantees this result. The futility of attempting to perform and being hobbled by the group contributes to stress for the highest performers.

The damage done by stress has been well documented in medical lore:

Stress that’s left unchecked can contribute to many health problems, such as high blood pressure, heart disease, obesity and diabetes.

If we look at the list of problems likely to kill us, those illnesses rank high on the list.

Long-term stress, such as that created by jobs, is the most damaging:

Health problems can occur if the stress response goes on for too long or becomes chronic, such as when the source of stress is constant, or if the response continues after the danger has subsided. With chronic stress, those same life-saving responses in your body can suppress immune, digestive, sleep, and reproductive systems, which may cause them to stop working normally.

…Routine stress may be the hardest type of stress to notice at first. Because the source of stress tends to be more constant than in cases of acute or traumatic stress, the body gets no clear signal to return to normal functioning. Over time, continued strain on your body from routine stress may contribute to serious health problems, such as heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and other illnesses, as well as mental disorders like depression or anxiety.

In nature, the role of stress is to prepare us to act when a threat is present. At jobs, however, the threat is both constantly present and unpredictable, so the stress becomes chronic because people are experiencing pain and fear about things they not only cannot control, but whose reasoning and motivations are hidden.

That chronic stress induces inflammation which can actually alter the genetics of the people involved:

Researchers found that chronic stress changes gene activity of immune cells before they enter the bloodstream so that they’re ready to fight infection or trauma — even when there is no infection or trauma to fight. This then leads to increased inflammation.

This phenomenon was seen in mice, as well as in blood samples from people with poor socioeconomic statuses (a predictor of chronic stress), reported the researchers from Ohio State University, the University of California, Los Angeles, Northwestern University and the University of British Columbia.

“There is a stress-induced alteration in the bone marrow in both our mouse model and in chronically stressed humans that selects for a cell that’s going to be pro-inflammatory,” study researcher John Sheridan, a professor at Ohio State University and associate director of the university’s Institute for Behavioral Medicine Research, said in a statement. “So what this suggests is that if you’re working for a really bad boss over a long period of time, that experience may play out at the level of gene expression in your immune system.”

We can see the effects of this mutational load through the links between inflammation and cancer, a disease caused by mutated cells going rogue and taking over the body like a parasitic organism:

However, while the genetic changes that occur within cancer cells themselves, such as activated oncogenes or dysfunctional tumor suppressors, are responsible for many aspects of cancer development, they are not sufficient. Tumor promotion and progression are dependent on ancillary processes provided by cells of the tumor environment but that are not necessarily cancerous themselves. Inflammation has long been associated with the development of cancer…Epidemiological evidence points to a connection between inflammation and a predisposition for the development of cancer, i.e. long-term inflammation leads to the development of dysplasia.

This genetic corruption can occur through stress alone, as previous articles have shown us, and simultaneously result in mutations and, if those go unchecked, cancers as well as other responses by the body such as autoimmune disorders. The body does not recognize its own mutated cells and attacks them, which is the opposite situation as with cancer, where it fails to recognize and attack its parasitic inner mutants.

Most diseases that are widespread and seemingly intractable in the modern time can be explained as the result of stress-induced inflammation. This could explain why, despite medical advances, sickness is so prevalent. Inflammation leads to other diseases, and stress creates an inability to regulate inflammation:

A research team led by Carnegie Mellon University’s Sheldon Cohen has found that chronic psychological stress is associated with the body losing its ability to regulate the inflammatory response. Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the research shows for the first time that the effects of psychological stress on the body’s ability to regulate inflammation can promote the development and progression of disease.

…Specifically, immune cells become insensitive to cortisol’s regulatory effect. In turn, runaway inflammation is thought to promote the development and progression of many diseases.

…”When under stress, cells of the immune system are unable to respond to hormonal control, and consequently, produce levels of inflammation that promote disease. Because inflammation plays a role in many diseases such as cardiovascular, asthma and autoimmune disorders, this model suggests why stress impacts them as well.”

With the loss of ability to regulate its inflammatory response, there is no system limiting the inflammation and, over time, this induces other disorders. With inflammation, common disorders become dangerous.

Not only can inflammation exacerbate existing diseases, but it can cause the brain to attack itself. Inflammation can lead to brain inflammation, memory loss and depression:

The researchers suspected that the stress was affecting the mice’s hippocampi, a part of the brain key to memory and spatial navigation. They found cells from mice’s immune system, called macrophages, in the hippocampus, and the macrophages were preventing the growth of more brain cells.

The stress, it seemed, was causing the mice’s immune systems to attack their own brains, causing inflammation. The researchers dosed the mice a drug known to reduce inflammation to see how they would respond. Though their social avoidance and brain cell deficit persisted, the mice had fewer macrophages in their brains and their memories returned to normal, indicating to the researchers that inflammation was behind the neurological effects of chronic stress.

In turn, this can have cognitive effects that also resemble problems of modern: the “memory hole” and social avoidance, suggesting that these rising trends may not be the result of cultural and economic pressures, but of biological changes — mutations — in our brains and the associated effects of inflammation and mutation.

This in turn could explain the reason for modern life to have become so toxic of late; while we have been pursuing the dream of wealth and technology, our inability to address our broken control structures and dark organizations has created a hellish life of stress that has been mutating us for centuries:

Penman labels the cultural characteristics that create and maintain a civilization as C. C includes industriousness, ability to cooperate, and moderation in food, drink, and sex. Chronic mild hunger produces hormonal, behavioral, and epigenetic changes that make people harder working and more cooperative. In societies with plentiful food similar effects can be achieved through religion and other social institutions: “Human societies, by a process of trial and error, have developed cultural practices which mimic the physiological effects of hunger” (14).

While C behaviors are required; “A successful civilization needs . . . some level of warlike aggression” (39). This should be disciplined aggression, group or collective assertion, not individual violence. Penman labels this component of civilization as V for vigor. Characteristics of V are a pioneering spirit, high morale, and the urge to expand and explore. The author offers Victorian Britain as a good mix of C and V.

V promoters include: intermittent (not chronic) stress, patriarchy, “an anxious but affectionate mother” and “exposure to adult authority in late childhood” (48). “One final V-promoter in human societies is control of women’s sexual behavior” (49). In summary, “the temperamental complexes labeled C and V can be considered the fundamental building blocks of civilization” (54).

Through epigenetic changes, natural stress produces strength and increases aptitude, but chronic stress as is found in jobs reduces strength and increases mutations, depression and disease. In other words, our addiction to jobs has been gradually mutating us into depressive, wimpy, mentally addled and unhealthy people. That fits with what we see going on out there.

Jobs produce anti-V stress which has the effect of entropy on the human mind and body. This realization fits with the observed real-world effects of jobs, especially on women, which seem to result in social disorders and depression:

Ms. Komisar’s interest in early childhood development grew out of her three decades’ experience treating families, first as a clinical social worker and later as an analyst. “What I was seeing was an increase in children being diagnosed with ADHD and an increase in aggression in children, particularly in little boys, and an increase in depression in little girls.” More youngsters were also being diagnosed with “social disorders” whose symptoms resembled those of autism — “having difficulty relating to other children, having difficulty with empathy.”

As Ms. Komisar “started to put the pieces together,” she found that “the absence of mothers in children’s lives on a daily basis was what I saw to be one of the triggers for these mental disorders.” She began to devour the scientific literature and found that it reinforced her intuition.

We have to ask here if autism, a disorder present since birth, is the result of the absence of the mother, or stress on the mother because she is working. Exposed to constant workplace stress, and suffering the mutations and inflammation of that in addition to the consequences of a lifestyle which involves little time to maintain a home, comfortable eating and sleeping, mothers may be passing common mutations to their children.

Work induces a type of paranoia in us because the tasks we do are not really related to the actual task, the environment is hostile, and we have to guess as to what will be rewarded and often, find that this is entirely arbitrary. To work around these events, people at jobs tend to put in longer hours and do extra work to cover all contingencies, forgetting that none of this is needed or helpful; it only exists for them to advance their careers, their managers to do the same and shareholders to have confidence in their investment in the company.

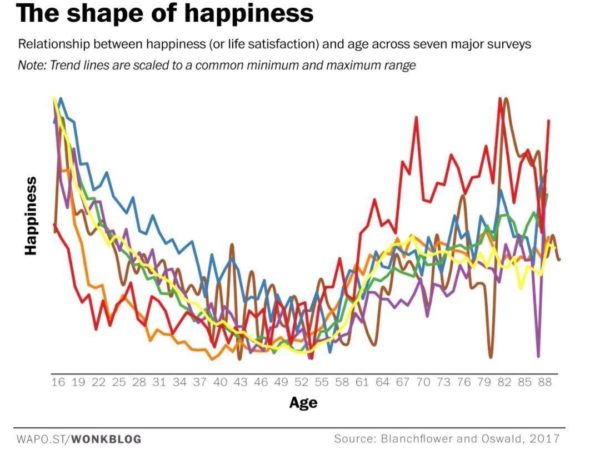

Notice how happiness peaks after retirement:

Jobs brought the downfall of the West. They make life subtly miserable, so that we feel it is improper to outright complain, especially since we have it better than others. But we notice that our irreplaceable time is slipping away and we are spending it on nonsense and appearance, and this induces resentment, instability, and hopelessness.

Western men became domesticated because jobs took over their lives. Originally, people cared for their own homestead and had some kind of calling — carpenter, farmer, hunter, soldier, priest, shoemaker — which ensured that they had money to use for what they could not produce at their home farms.

But then, for people at the top, society became administrative as, thanks to advances in medicine and hygiene, the lower echelons of society swelled in number. This introduced a managerial type of society where a few smart people dedicated most of their time to reigning in the burgeoning masses, who like all lower-IQ people were highly individualistic and thus acted in chaotic ways, requiring restraint.

Once the West declared “freedom” and “equality” to be its goals, this process accelerated even further.

At this point, jobs have dominated the West and with them, through the denial of inner traits, the use of external manipulation has essentially domesticated and infantilized people, increasing atomization by eliminating ways that they can actually trust others. Now we are all actors on stage.

Jobs take up all of our time. Your average person prepares for an hour in the morning, commutes for another half hour, then stays late in order to qualify for a promotion. When they get home, after another half-hour commute, they are thinking about work and what people said and did. At this point, they have only a few hours before they must go to sleep, get up and do it the next day, for at least 71% of the days of the week.

When the weekend comes, this person is unprepared. Two whole days, with at least half of the first one taken up with filing taxes, researching new products, home repairs, stocking up on groceries, studying for a certification for work, fixing broken gadgets, cleaning the house, taking the pets to the vet, ferrying children to activities, doing laundry, paying bills, and a few thousand other little tasks that eat time and leave the person somewhat stranded.

On top of that, the conditioning kicks in. People whose days are marked by routine and external obligation suddenly have no idea what to do with themselves when they do have free time. As a result, the weekend presents stress as well: it is rare time, precious and necessary, but as people with no idea how to best spend that time, most people end up uncertain as to what to do, and as a result, wasting their time on what other people seem to be doing even if it does not fit them.

This psychological conditioning spreads through all aspects of life. Domesticated people cannot thinking critically, cannot analyze and cannot make decisions of their own; they always defer to the group, and then feel cheated because the results that work for an average person rarely work for any given individual. In politics, such as when they vote, or in personal behaviors, they emulate others, and then end up feeling terrible about the time they seem to have no control over, slipping through their fingers.

It is not surprising that a population subjected to jobs is deteriorating:

Data released last week suggest Americans’ health is declining and millions of middle-age workers face the prospect of shorter, and less active, retirements than their parents enjoyed.

The U.S. age-adjusted mortality rate — a measure of the number of deaths per year — rose 1.2 percent from 2014 to 2015, according to the Society of Actuaries. That’s the first year-over-year increase since 2005, and only the second rise greater than 1 percent since 1980.

…For those with a retirement age of 66, 11 percent already had some kind of dementia or other cognitive decline at age 58 to 60, according to the study. That’s up from 9.5 percent of Americans just a few years older, with a retirement age between 65 and 66.

Cognitive decline and increased mortality from disease are consistent with the stress-induced inflammation and genetic mutation that is discussed above. Although our minds are conditioned not to see it because we worship work as a means of being equal citizens, the theory lines up with reality.

Despite having all of our technology, wealth, and power, we are still working long hours in stressful conditions making ourselves neurotic. We are driven by a sense of labor by the pound, or what the employer is willing to pay for, instead of results, which are discerned in finer measurements and regulated not by the power of the manager, the shareholder or the employee but by the market, which is part of that scary Real World which reacts to what we do, often not in the ways we intended.

We live in a bubble: between the time when we act, and the time when results appear, managers and shareholders and the buying public reward us. Our social group claps us on that back and says attaboy. The money flows in, and then only later do we see the actual consequences. This insulates us from ever being really wrong, and allows for almost everyone to stay employed with no risk.

This creates false productivity based on the amount of economic activity we generate within the time-span of the bubble, not how much actual value we produce. This corresponds to the general link in humanity between solipsism and socialization where as long as we generate a buzz among others, we are seen as successful, because a self-referential society cares only about shared feelings and perceptions, not real productivity because as a society we are wealthy enough that the bread and steaks will keep coming no matter what we do.

As a result, people have found that the more hours they work, the more false productivity is created, and so they are essentially forced to work long hours for monetary reward despite this being, in the long term, economically irrelevant:

Recently, economists at Purdue and the University of Copenhagen made a clever attempt to clear up the question. They looked at Danish manufacturing companies where overseas sales increased unexpectedly because of changes in foreign demand or transportation costs between 1996 and 2006. These constituted a set of natural experiments. At firms where exports spiked, there was suddenly a lot more work to do, a lot more things to sell. This put the squeeze on employees, who became measurably more productive — but also started to have more health problems.

“The medical literature typically finds that people who work longer hours have worse health outcomes — but we try to distinguish between causality and correlation,” said Chong Xiang, an economics professor at Purdue and co-author on the paper, along with David Hummels and Jakob Munch. A draft was released this week by the National Bureau for Economic Research.

…If external forces caused a company’s exports to rise by, say, 10 percent, female employees were about 2.5 percent more likely to be treated for severe depression, and 7.7 percent more likely to take heart attack or stroke drugs. For context, about 4 percent of women overall were being treated for severe depression and 1 percent of women were on heart attack or stroke medication. These conditions are not very common, but job strain caused a measurable, statistically significant bump in prevalence.

In other words, the more you work, the less healthy you are. The more you succeed, the more likely you are to become sick, sterile and non compos mentis. The more you rely on your economy to guide you, the more it will lead you to doom; the more you rely on what other people think, the more you will be forced to go through mindless rituals of no significance.

We see an insight into The Human Problem through this. Like our fast money policies, it relies on a self-referential measurement, or assessing what placates the group (socialization, utilitarianism, rationalization) rather than what achieves the right results in reality, because the latter cannot be universally assessed.

This internal measurement leads to us chasing phantoms, such as measurements of productivity instead of productivity itself, and these are rewarded because other people are deciding what should be rewarded and they are using the same measurements. However, the map is not the territory… and the sensation is not the reality. This creates a spiral of unreality where what makes others feel safe, whether managers or shareholders, becomes the new reality, and the actual reality is forgotten.

It is no surprise that most people feel their jobs are pointless and that this increases the farther up in the hierarchy you go. We are a society dedicated toward nonsense work because it is not purposive toward a goal, but is designed as appearance, to make others feel good about the situation and therefore, to reward those doing the nonsense “work.”

In a 2013 survey of 12,000 professionals by the Harvard Business Review, half said they felt their job had no “meaning and significance,” and an equal number were unable to relate to their company’s mission, while another poll among 230,000 employees in 142 countries showed that only 13% of workers actually like their job. A recent poll among Brits revealed that as many as 37% think they have a job that is utterly useless.

This is consistent with other even more cynical measurements which found that most Americans are not “present” at work because the work they are doing is unrelated to reality:

More broadly, just 30 percent of employees in America feel engaged at work, according to a 2013 report by Gallup. Around the world, across 142 countries, the proportion of employees who feel engaged at work is just 13 percent. For most of us, in short, work is a depleting, dispiriting experience, and in some obvious ways, it’s getting worse.

In other words, most people know that their jobs are pointless, but by the same token, they still suffer the stress of these jobs which cannot be unrelated to the lack of utility and purpose of those jobs. Thus, like patients strapped to a gurney and bled out via a transfusion line, the average modern person knows that they are engaged in nothing of value but are dependent on it, so suffer stress and the existential void of knowing they are wasting their time on nonsense to appease the lower echelons of society. They are slaves, sacrifices and scapegoats, these workers.

The real crisis of this is that the penalty falls unequally. The intelligent realize their time is being wasted, become despairing and die out; fools who have nothing better to do see nothing wrong, and so thrive despite being in horrible circumstances. Jobs create a dysgenic force that rewards the fool and punishes the intelligent.

The intelligent, in contrast to those who must spend their time fascinated by what others do, require more time outside of work to organize their thoughts and gain clarity on what is vital:

Findings from a US-based study seem to support the idea that people with a high IQ get bored less easily, leading them to spend more time engaged in thought.

And active people may be more physical as they need to stimulate their minds with external activities, either to escape their thoughts or because they get bored quickly.

More intelligent people require more time to think, and jobs interrupt this by spamming their most active hours with tasks that have nothing to do with reality, and therefore, baffle the mind with nonsense.

This explains the downfall of civilizations: as they grow, the upper echelons become dedicated to their maintenance, taking on roles that stultify them, stress them, mutate them and make them ill. It is no wonder that every human civilization has failed; they have self-destructed through the black magic of jobs.

As conservatives, or those who conserve the best of the past and carry it forward into the future, we must address the crisis of jobs: mutations, disease, boredom, domestication, and existential misery.

Our most direct attack comes through replacing the false managerial hierarchy of “accountability” with something more exact, namely a hierarchy that addresses results in reality. This requires — gods forbid! — slowing down our cycle of perception and waiting for actual results to appear instead of using the social measurement of intermediate targets.

This requires us to do away with the illusion of meritocracy, or the idea that we can take “equal” humans and test them to determine who is good. This measures only external attributes like obedience, and misses out on the need to find out what people are made of within so that they do not have to be constantly monitored and penalized for not meeting the token objectives required by a meritocratic system.

In an indirect way, “work hard, pray hard” is a confirmation of egalitarianism: it holds that we are all equal and that the differences between us consist of how hard we work and how righteously we behave, when in fact intelligence matters more than labor by the pound in terms of results, and righteous behavior arises from the ability to understand why morality and qualitative improvement are important. But for those wielding “work hard, pray hard,” this pragma enables them to both deflect challenges to their possessions — “I worked hard for this!” — and to subtly explain themselves as morally superior, because after all, they worked harder and prayed harder than others, therefore if those are their values, they deserve what they have, and they can explain it without the socially-unpopular but realistic notion that some are born smarter and better than others.

Instead of having this indirection work against us, we can make it work for us by instead acknowledging that humanity is an evolutionary struggle between our smarter people and our dumber ones. The lower echelons will always be destructive because they cannot understand anything above their station, therefore will see it as unnecessary; much as the third world is the most individualistic place on Earth, our own homegrown proles are more individualistic and thus greedy, selfish, solipsistic, corrupt and perverse than those above them.

The Human Problem occurs whenever a group of humans form because social pressures reward accepting the stupid and including it, instead of following the law of nature, where a group that excels will break away. This social pressure exists because of fear of the herd; if a smarter group breaks away, it will be by the law of quality-versus-quantity less numerous than the herd, and the herd will then show up and dominate through superior numbers. Even highly proficient and trained soldiers cannot overcome odds of twelve-to-one or greater, which was the lesson of WW2 and perhaps why the world shifted so hard Left afterwards; the Left pacifies the herd by including them, and then allows the wealthy to buy their way into the good graces of the herd, although this backfires because then the herd controls the elites.

Once we accept that we are not equal, and that some are better than others by virtue of having greater force of intellect and force of character in parallel, meaning that both are required — this filters out the dot-com “geniuses” and clever shopkeepers — we can set up a hierarchy where the levels of society are acknowledged. This takes the form of both an aristocratic hierarchy, and caste levels to society; at the very top are the people who make decisions for the culture, and these tend to — in the way of actual genius, not the fake genius of the dot-com boffins and clever merchants — focus on qualitative improvement instead of “new” unproven theories. Slightly below them are the good and decent people, and these become local leaders through the manorial system. Only this reverses the problem of human decline, which occurs through the war of the many less-bright against the honest and decent brights who create and develop civilization.

Hierarchies of this nature lead to the manorial system as we see in the classic cultures of Western Europe and the ancient lands of Rome and Greece:

the manor system in core austrasia changed pretty rapidly (already by the 500s) to one in which the lord of the manor (who might’ve been an abbot in a monastery) distributed farms to couples for them to work independently in exchange for a certain amount of labor on the lord’s manor (the demesne). this is what’s known as bipartite manorialism. and from almost the beginning, then, bipartite manorialism pushed the population into nuclear families, which may for some generations have remained what i call residential nuclear families (i.e. residing as a conjugal couple, but still having regular contact and interaction with extended family members). over the centuries, however, these became the true, atomized nuclear families that characterize northwest europe today.

for the first couple (few?) hundred years of this manor system, sons did not necessarily inherit the farms that their fathers worked. when they came of age, and if and when a farm on the manor became available, a young man — and his new wife (one would not marry before getting a farm — not if you wanted to be a part of the manor system) — would be granted the rights to another farm. (peasants could also, and did, own their own private property — some more than others — but this varied in place and time.) over time, this practice changed as well, and eventually peasant farms on manors became virtually hereditary. (i’m not sure when this change happened, though — i still need to find that out.) finally, during the high middle ages (1100s-1300s) the labor obligations of peasants were phased out and it became common practice for farmers simply to pay rent to the manor lords.

In other words, there was always a higher-IQ lord who could regulate the peasants, and by restricting resources in the form of land, keep their population down and keep them from forming the thronging masses that the Greeks recognized arose in cities, and quickly adopted the characteristics of herd rule. Since the lords owned all the land, any activity on that land had to be approved by a lord, and pay tax to that lord, insuring that any wealth generated would then be put back into the community through the hands of the people least likely to waste it.

Manorialism and hierarchy improve jobs by limiting them. Perhaps future corporations will be located on manors, and each corporation will have an assigned lord on whose land they dwell, and shareholders will be limited to those of the upper classes, which will avoid the “race to the bottom” that occurs where corporations compete merely in terms of popularity, which grants them the media mentions and trend buzz required to wake up a population to their products despite being as a population over-saturated in terms of product options, advertising, trends and other distractions.

A social order of this nature also limits social mobility which means that people will stop constantly agitating for more money and power as a means of raising social status. In addition, it restricts commercial impulses — shopkeeping, merchants and other clever people — by placing them firmly among the lower castes, albeit a high lower caste, and by doing so removes the focus on work, money and commerce to the point that it takes over society, such as we see in Western “civilization” today.

In addition, by concentrating wealth among those who are most discerning, this type of community order enables civilization to pay people to do unprofitable things like make great art instead of pop culture, curate ancient ruins, care for forests, watch over lonely places, keep spaces clean and engage in cultural activity, customs and events.

We can see remnants of this ancient order in the UK, where the lords owned all the land and preserved huge amounts of it in its natural state as “hunting preserves” which were infrequently used. This created a vast “green belt” across the nation where wildlife was safe at least on the population level — if you did not mind a few dead foxes here and there — and interrupted the constant growth of cities and suburbs like a cancer spreading across the land.

By relaxing the pressures and attitudes that create modern jobs, the caste/aristocracy/manor way of life makes jobs more pleasing and less likely to take up all of our time. Medieval peasants spent a fraction of the time working that we do now, and more time living; aristocrats as well, the people who by their greater intelligence need more time off to simply learn how to think and refresh their core of wisdom, spent less time engaged in frustrating baby-sitting and more time connecting to the ideas behind culture, the reasons why that have to be re-learned every generation because they cannot be conveyed in written text.

Only when combined threats — Mongol invasions, plagues, religious division, Islamic invasions, wars — destabilized the aristocracy did the clever-but-not-bright middle classes manage to buy themselves into the power system and then weaponize the proles against the aristocrats. The Church facilitated this by trying to be a dual system of power to that of the kings, and in so doing, fragmented the power of the kings and let evil in through the back door.

As anyone who studies The Human Problem knows, this problem repeats itself time and again in all human organizations, or groups of more than two people. Unless a hierarchy is established, the rest oppress the best, and because this mass are not the best, they make increasingly horrible decisions. Every civilization dies by suicide resulting for collective insanity as people contort their thinking to fit what is popular, and the whole society goes over the cliff chasing an illusion, a phantom, an oasis and a chimera.

Reversing the progress of The Human Problem also frees us from mass culture, where whatever pleases the largest group wins out and so a “race to the bottom” exists for the most venal, crass and debasing “art” because that is what is profitable. This in turn generates a trend-based culture where each group, including corporations, hopes for the “big score” that comes with creating something that is vastly popular and becomes a trend. When these fads go big, they follow an arc by which The Human Problem ultimately infiltrates them from within, which makes profit for those who get in early and sell out right before the peak, but then bankrupts anyone who hangs on to the asset. The best example of this so far may be MySpace, which at its peak sold for $500m only to be worth $50m a few years later.

We have learned from modern time that we cannot use formal organization to tame our problems because it is too easily gamed. The rules, laws, incentives, punishments and procedures only take effect after a crisis have occurred, and so represent attempts to fix effects directly instead of looking to their underlying causes in the moments leading up to the creation of the disaster. Jobs fit within this perfectly well: to improve workplaces, we regulate workplaces, instead of looking at the underlying pressures that create them in the form we see them.

Conservatives, if they stay true to their principles, must realize that our society began failing for existential reasons and crept away from virtue in order to pacify the herd, include everyone, and try to replicate classical civilization by instead relying on mobilized masses. This mass culture creates the horror that is jobs/work, and to undo it, we must reverse its causes and focus on hierarchy instead of equality, because equality creates conformity and makes us treat ourselves as products on an assembly line, and it is from this outward-in order of regulated herd behavior that the horror of the workplace arises.

Tags: anti-work, control, crowdism, jobs, jobs are jails, manorialism, work