You Are Reading Plato Incorrectly

The Right, gods help it, has no clue about analyzing documents. It can handle direct linear interpretation like reading code, but gets befuddled when it comes to law, literature, or philosophy. This is doubly unfortunate because in the classics of those genres, some of the vital aspects of conservatism and indeed human life lurk.

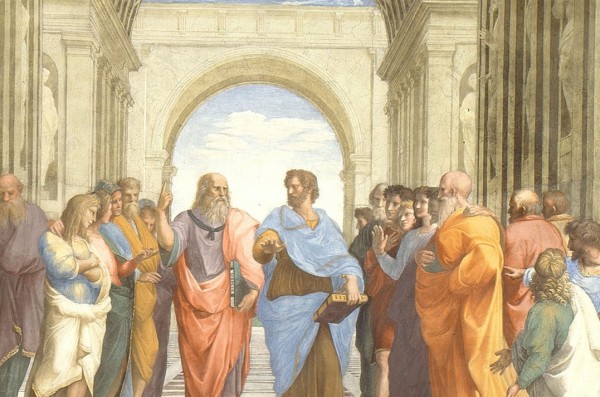

For example, we frequently hear that Plato — the cornerstone of Western thought, centuries before Christ and Judaism as an organized religion — “advocated” a Communist-style, Star Trek like Utopian state where wise Guardians managed the proles according to Huxleyesque scientific methods.

Conservatives consider themselves witty for saying this as if they finally found the smoking gun that lets them argue for their favorite form of prole-rule, which is just like Leftist prole-rule but with churches and capitalism. They want the triune herd individualist ideal: I do whatever I want, everyone else pays, someone else cleans up.

But with churches and free markets, of course.

More likely they argue against Plato because they fear him. Plato is a spokesman for nature and the eternal, which means that he denies the human illusions by which most people live, seeing them not only as crutches but as paths to a lesser life than can be offered through a realistic approach.

In The Republic, Plato talks about a Utopian state, but he does so to make a point through a thought-experiment:

In the Republic, which have been nothing more than a thought experiment, he conceived of an ideal state ruled by a small number of people selected, after close observation and rigorous testing, from a highly educated elite.

We do not know the full meaning of the author because of a missing word; was it “may have been,” or “must have been” that the author intended? Luckily Plato himself provides the answer, but it requires the skill of document analysis, which is something most cannot do even if they have the “education” for it.

Plato’s Republic flows like a symphony: it starts slow, launches into a conflict of themes, the opposites meet and resolve, then things chill out for a bit before a final return to the theme in thunderous power. The narrative begins with a social scene in which Socrates converses with an older man and they begin to discuss justice as a concept:

For let me tell you, Socrates, that when a man thinks himself to be near death, fears and cares enter into his mind which he never had before; the tales of a world below and the punishment which is exacted there of deeds done here were once a laughing matter to him, but now he is tormented with the thought that they may be true: either from the weakness of age, or because he is now drawing nearer to that other place, he has a clearer view of these things; suspicions and alarms crowd thickly upon him, and he begins to reflect and consider what wrongs he has done to others. And when he finds that the sum of his transgressions is great he will many a time like a child start up in his sleep for fear, and he is filled with dark forebodings. But to him who is conscious of no sin, sweet hope, as Pindar charmingly says, is the kind nurse of his age:

Hope, he says, cherishes the soul of him who lives in justice and holiness and is the nurse of his age and the companion of his journey; –hope which is mightiest to sway the restless soul of man.

How admirable are his words! And the great blessing of riches, I do not say to every man, but to a good man, is, that he has had no occasion to deceive or to defraud others, either intentionally or unintentionally; and when he departs to the world below he is not in any apprehension about offerings due to the gods or debts which he owes to men. Now to this peace of mind the possession of wealth greatly contributes; and therefore I say, that, setting one thing against another, of the many advantages which wealth has to give, to a man of sense this is in my opinion the greatest.

Well said, Cephalus, I replied; but as concerning justice, what is it? –to speak the truth and to pay your debts –no more than this? And even to this are there not exceptions? Suppose that a friend when in his right mind has deposited arms with me and he asks for them when he is not in his right mind, ought I to give them back to him? No one would say that I ought or that I should be right in doing so, any more than they would say that I ought always to speak the truth to one who is in his condition.

You are quite right, he replied.

But then, I said, speaking the truth and paying your debts is not a correct definition of justice.

When Socrates says “speaking the truth and paying your debts is not a correct definition of justice,” he brings out the theme of the book: the ideal state of mind for the individual produces the ideal state of civilization, and this can only be recaptured by seeing goodness (including justice) on a level above human concerns.

Did you wonder why most of Christianity and pre-Christian Jewish thought was cribbed from the Greeks? This is why: Plato discusses the importance of a goal beyond the self and others, such as a type of order or structure that promotes thriving instead of directly commanding this.

Under the mixed-race Jews, this was distilled down to “humanism” in the form of tikkun olam, but under the half-Roman Christ that got modulated into the idea of “faith,” or as Kant would say, universal maxim or order.

If Plato has an overarching theme, it is that we live in a relative universe, and therefore opposites produce each other. Death begets life, life brings death. From this he argues that our physical reality is the product of an opposite, too, based in structure (forms, order, organization) instead of tangible materiality.

Plato sees the opposites at the core of relativity as central to understanding the structure (form) of the world, instead of being befuddled by its aesthetic and material presentation (maya in the Hindu lexicon):

Are not all things which have opposites generated out of their opposites? I mean such things as good and evil, just and unjust-and there are innumerable other opposites which are generated out of opposites. And I want to show that this holds universally of all opposites; I mean to say, for example, that anything which becomes greater must become greater after being less.

In that sense, Plato is an antithesis to Jewish and all other third-world thought. He emphasizes the transcendent, or seeing the process of life beneath the surface of sensations, over the humanist, novel, immediate, tangible, material, and social.

Although Christ adopted some of this, his religion was popularized and misinterpreted into neoplatonism, which is the idea that Heaven and Earth are opposites, so pick Heaven and reject physical life and its commonsense, naturalistic rules. This inverts Plato.

Inversion occurs because social groups prioritize exceptions. If something is known to be true, that irks the human ego, so individualists find what they argue is an exception and try to use that to destroy the rule of what is true. Over time, the focus on dealing with exceptions first inverts the original rule into its opposite.

Neoplatonism is an opposite to Plato. (This sentence gets its own line because it is both obvious and widely denied.)

Where Platonism emphasizes the metaphysical creating the physical in a feedback loop of relative opposites, neoplatonism emphasizes the metaphysical at the expense of the physical, heading into territory more populated by superstition and schizophrenia than sanity. Neoplatonism will always be more popular however.

Its popularity comes from its appeal to people in permanent civilizations, which necessitate systems or specialized sets of procedures to keep the system running. Once civilization becomes permanent, it requires specialized labor roles and procedures to be done in the right order.

When you set up a system that has a single path to success, people game the system and start acting exclusively in self-interest because they have been forced to engage with it and they come to resent it. They hide behind self-pity as a way to justify their vengeance. This is what means-over-ends thinking produces.

This is why our cutting edge thinkers these days say that there are no conspiracies; there is only careerism. Careerism is me-first self-interest caused by being told what to do. People hate that, but need it, so they have a sort of BDSM relationship with it, both rebelling against it and clinging to it.

In a sane society, your aristocrats aim for transcendental goals and treat everything else on a case-by-case basis according to patterns they observe in nature, from which they also derive their spirituality. They reward the good, smite the bad, and leave everyone else tf alone to pursue their unequal destinies.

A really intelligent society would filter out careerists and stuff them into the plastic shredders, wood chippers, gas chambers, drowning pools, or other methods of removal. Me-first people are an abomination unto the Earth, but so far people who always defer to peer pressure and therefore form a Crowd or dark organization.

Plato, a gentle soul, never made it to that point, and this was perhaps a personal revulsion at killing more than anything else. I join him in that sentiment, but recognize the logicality of having a substitute for natural selection, which kills off the unrealistic so that the realistic breed more and dominate the genome of the species.

If humanity Holocausted its insane, career criminal, retarded, sociopathic, psychopathic, neurotic, me-too, and narcissistic people, it would be a tenth of its size and a few hundred times its current quality. We would not be facing The Ecocide and the slow degradation of our species back into hominid status.

Plato — like your author — was obsessed with civilization decay and how to avoid it, pointing out the vast loss of knowledge that comes with civilization collapse, analogized here as natural collapse which he also portrayed in the Republic with the parable of Atlantis:

The fact is, that wherever the extremity of winter frost or of summer does not prevent, mankind exist, sometimes in greater, sometimes in lesser numbers. And whatever happened either in your country or in ours, or in any other region of which we are informed-if there were any actions noble or great or in any other way remarkable, they have all been written down by us of old, and are preserved in our temples. Whereas just when you and other nations are beginning to be provided with letters and the other requisites of civilized life, after the usual interval, the stream from heaven, like a pestilence, comes pouring down, and leaves only those of you who are destitute of letters and education; and so you have to begin all over again like children, and know nothing of what happened in ancient times, either among us or among yourselves. As for those genealogies of yours which you just now recounted to us, Solon, they are no better than the tales of children. In the first place you remember a single deluge only, but there were many previous ones; in the next place, you do not know that there formerly dwelt in your land the fairest and noblest race of men which ever lived, and that you and your whole city are descended from a small seed or remnant of them which survived. And this was unknown to you, because, for many generations, the survivors of that destruction died, leaving no written word. For there was a time, Solon, before the great deluge of all, when the city which now is Athens was first in war and in every way the best governed of all cities, is said to have performed the noblest deeds and to have had the fairest constitution of any of which tradition tells, under the face of heaven.

His point here was that permanent civilization is fragile and tends to self-destruct, after which humanity has to start over and then encounters the same problems. The “stream from heaven” is an analogy for time, which is what water often represents, as well as memory and dream, in ancient writings.

This is riffed on in Christianity as a rejection of means-over-ends thinking; in one passage, the holy rejects “going through the motions” and following rabbinical law in favor of pursuing justice:

21 I hate, I despise your feast days, and I will not smell in your solemn assemblies.

22 Though ye offer me burnt offerings and your meat offerings, I will not accept them: neither will I regard the peace offerings of your fat beasts.

23 Take thou away from me the noise of thy songs; for I will not hear the melody of thy viols.

24 But let judgment run down as waters, and righteousness as a mighty stream.

In the Judaic view, destruction comes in the form of waters that erase all that is bad. This alludes to the Platonic concept of justice as the transcendental maxim not the Abrahamic humanist view, and the tendency of time to obliterate civilizations which aim for sophistry or Pharisaic law instead of the ends-over-means pursuit of the good.

The Republic is a book about justice and what is good, leading to “the best life” as Socrates summarizes early on, in parallel between the individual mind and the civilization. Plato straight up tells us that he is using the Utopian society as a metaphor or thought experiment for discovering justice:

For I am in a strait between two; on the one hand I feel that I am unequal to the task; and my inability is brought home to me by the fact that you were not satisfied with the answer which I made to Thrasymachus, proving, as I thought, the superiority which justice has over injustice. And yet I cannot refuse to help, while breath and speech remain to me; I am afraid that there would be an impiety in being present when justice is evil spoken of and not lifting up a hand in her defence. And therefore I had best give such help as I can…

Seeing then, I said, that we are no great wits, I think that we had better adopt a method which I may illustrate thus; suppose that a short-sighted person had been asked by some one to read small letters from a distance; and it occurred to some one else that they might be found in another place which was larger and in which the letters were larger –if they were the same and he could read the larger letters first, and then proceed to the lesser –this would have been thought a rare piece of good fortune.

Very true, said Adeimantus; but how does the illustration apply to our enquiry?

I will tell you, I replied; justice, which is the subject of our enquiry, is, as you know, sometimes spoken of as the virtue of an individual, and sometimes as the virtue of a State.

True, he replied.

And is not a State larger than an individual?

It is.

Then in the larger the quantity of justice is likely to be larger and more easily discernible. I propose therefore that we enquire into the nature of justice and injustice, first as they appear in the State, and secondly in the individual, proceeding from the greater to the lesser and comparing them.That, he said, is an excellent proposal.

And if we imagine the State in process of creation, we shall see the justice and injustice of the State in process of creation also.I dare say.

When the State is completed there may be a hope that the object of our search will be more easily discovered.Yes, far more easily.

But ought we to attempt to construct one? I said; for to do so, as I am inclined to think, will be a very serious task. Reflect therefore.I have reflected, said Adeimantus, and am anxious that you should proceed.

A State, I said, arises, as I conceive, out of the needs of mankind; no one is self-sufficing, but all of us have many wants. Can any other origin of a State be imagined?

In the end, Plato points out that civilizations go through a life cycle in which democracy is the death-stage and drives people insane:

And is not their humanity to the condemned in some cases quite charming? Have you not observed how, in a democracy, many persons, although they have been sentenced to death or exile, just stay where they are and walk about the world –the gentleman parades like a hero, and nobody sees or cares?

Yes, he replied, many and many a one.

See too, I said, the forgiving spirit of democracy, and the ‘don’t care’ about trifles, and the disregard which she shows of all the fine principles which we solemnly laid down at the foundation of the city –as when we said that, except in the case of some rarely gifted nature, there never will be a good man who has not from his childhood been used to play amid things of beauty and make of them a joy and a study –how grandly does she trample all these fine notions of ours under her feet, never giving a thought to the pursuits which make a statesman, and promoting to honour any one who professes to be the people’s friend.

You will recognize your current Clown World in the description he offers.

He identifies the beginning of this process as the transfer from ends-over-means transcendental thinking to means-over-ends material and power-oriented thinking:

When discord arose, then the two races were drawn different ways: the iron and brass fell to acquiring money and land and houses and gold and silver; but the gold and silver races, not wanting money but having the true riches in their own nature, inclined towards virtue and the ancient order of things. There was a battle between them, and at last they agreed to distribute their land and houses among individual owners; and they enslaved their friends and maintainers, whom they had formerly protected in the condition of freemen, and made of them subjects and servants; and they themselves were engaged in war and in keeping a watch against them.

In the Platonic world, only the transcendental aligns to “the forms” or the structure of reality through cause-effect analysis, and when we deviate from that, we stagger through a series of decay-stages culminating in democracy, at which point everyone goes insane.

He developed a full theory of relativity and pattern-based polycausality which is the basis of his theory of forms:

Plato’s conception of forms is related to his ideas of cause/effect relationships. In his view, effects are the visible manifestations of causes, and those causes are often separated from their effects by a chain of proximate causations distributed through time. These are invisible in the sense that when you see the effect, it is not immediately obvious what its cause was. Plato suggests that multiple forces interacting result in effects, so there is not a single root of a “cause” so much as there is a collision of forces producing a causal event.

Modern people have tended to react to Plato’s theory of forms and his explanation of them, his cave allegory, as an allusion to dualism. In the modern view, if a cause is not material, it must exist elsewhere.

In an ancient view however, natural forces exist and their interaction produces the need to which a form is adapted. For example, a hammer is perfectly suited to the human hand and the need to bash nails. In a more complex sense, we design airplane wings to gain lift from the passage through air, and this is a result of fluid dynamics, which itself results from the properties of matter.

Plato’s point is that all of matter has a root in a system of organization that underpins every material aspect of the universe, and that this system is not necessarily “different” from material, because it may not exist “per se” in the way material does, but emerges from the interaction of material parts. In other words, the organization of material hints at an abstraction that only exists as brought into momentary existence through the interaction of matter.

He sees means-over-ends thinking as more popular because it enables individualism, but as ultimately destructive to philosophy, or the accumulation of knowledge about the workings of our world in the abstract:

For this reason, conservatives see “the good” not as “the popular” but as the eternally good, meaning both in the long-term and that in every age of humankind, what will produce results above the mediocre norm. As popular wisdom dictates, we either aim high in life or getting dragged down by entropy, stagnation and the steady erosion brought on by time. Conserving means not preserving a past state, but having a future aim that can never be fully achieved because that means we are always pointing in an upward direction.

This leads to a clash with popular morality. Most people want a morality of “protect the weaker” because, as individuals, they fear falling short of social standards or required performance at a task. For this reason, they envision themselves as the weaker and reason that if society protects the weaker, they personally will never face consequences. The eternally popular idea in humanity is: receive the benefits of civilization, but take on none of the burdens, a mentality we might call “anti-accountability.”

Popular morality regulates by method. Murder is bad; therefore, all killing — a method — is bad. This introduces hilarious inconsistencies when we go to war, execute murderers or defend ourselves because those are killings, which are bad, but can often have good results. This hopelessly confuses the issue, which is not method but results. Killing a bad person is good, but killing a good person is bad, to use the simplistic nomenclature of popular morality.

Extrapolating from this, conservatism consists of an aim for the eternally true, exemplified in transcendentals like “the good, the beautiful, and the accurate/real/true,” as other philosophers summarized. Only by escaping Crowdism do civilizations — and their genetic core of peoples — survive.

Plato would see egalitarianism and its derivations like Communism, diversity, woke, feminism, civil rights, collectivism, etc. as forms of individualism in groups based on the lowest common denominator, personal fear, to which people respond with self-pity and me-first self-interest.

His famous cave metaphor refers to how humanism replaces realism and produces an illusory consensual hallucination of universal truth, values, and communications that befuddles humanity and leads them to their destruction via ever-flowing streams from the heavens.

Consider how this destruction manifests in liberal reforms that always invert their good intentions and become tyrannical:

On September 17th, a Law of Suspects was introduced allowing for the arrest of anyone whose conduct suggested they were supporters of tyranny or federalism, a law which could be easily twisted to affect just about everyone in the nation. Terror could be applied to everyone, easily. There were also laws against nobles who had been anything less than zealous in their support for the revolution. A maximum was set for a wide range of food and goods and the Revolutionary Armies formed and set out to search for traitors and crush the revolt. Even speech was affected, with ‘citizen’ becoming the popular way of referring to others; not using the term was a cause for suspicion.

It’s usually forgotten that the laws passed during the Terror went beyond simply tackling the various crises. The Bocquier Law of December 19th, 1793 provided a system of compulsory and free state education for all children aged 6 – 13, albeit with a curriculum stressing patriotism. Homeless children also became a state responsibility, and people born out of wedlock were given full inheritance rights. A universal system of metric weights and measurements was introduced on August 1, 1793, while an attempt to end poverty was made by using ‘suspects’ property to aid the poor.

However, it is the executions for which the Terror is so infamous, and these began with the execution of a faction called the Enrages, who was soon followed by the former queen, Marie Antoinette, on October 17th and many of the Girondins on October 31st. Around 16,000 people (not including deaths in the Vendée, see below) went to the guillotine in the next nine months as the Terror lived up to its name, and around the same again also died as a result, usually in prison.

In Lyons, which surrendered at the end of 1793, the Committee of Public Safety decided to set an example and there were so many to be guillotined that on December 4th-8th, 1793 people were executed en masse by cannon fire. Whole areas of the town were destroyed and 1880 killed. In Toulon, which was recaptured on December 17th thanks to one Captain Bonaparte and his artillery, 800 were shot and nearly 300 guillotined. Marseilles and Bordeaux, which also capitulated, escaped relatively lightly with ‘only’ hundreds executed.

Looks like Plato had a point after all. His “Utopia” was designed to point out that once we deviate from a transcendental goal, no amounts of means-over-ends thinking — he argues toward the absurd extremes deliberately — will fix what has gone wrong until we actually fix our heads and orient toward the good again.

Tags: civilization collapse, crowdism, dark organization, democracy, egalitarianism, maya, plato, the republic