American Nativism

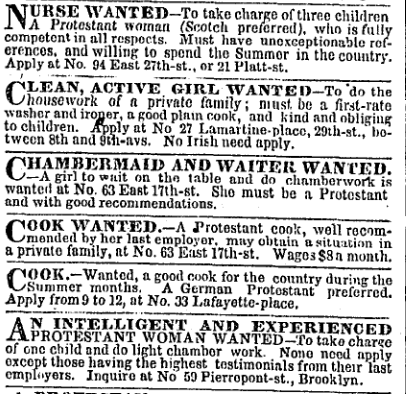

Image from “No Irish Need Apply” at The New York Times.

Most people do not realize that “populism” was originally a movement called American Nativism which defended the founding WASP — English, Scots, north German, Dutch, north French, and Scandinavian — population against the incursion of Souther, Mediterranean, and Eastern Europeans, who are racially mixed with Asiatics and/or North Africans.

This crisis kicked off shortly after the founding of the nation, once the pioneers got the hard work done, and swelled the established cities of the East Coast, leading to a need for cheap raw materials and therefore, the lead-up to the Civil War.

At first, in the 1750s, Americans found themselves concerned by the arrival of south Germans, who are of a different ethnic stock than the Nordic north Germans, since the north Germans were a mixture of Nordic with small amounts of Brünn and Borreby, while south Germans were more Alpinid, following the racial history of Germany:

In view of the history of Germany, it is not surprising that the modern German people should be divided regionally on a racial basis. Since the only part of the Reich which is old Germanic country is the extreme north-west, one should expect to find early Germanic racial types in the numercal ascendancy in that region alone, but their occurrence as individuals is to be expected everywhere, and is so found.

The problem of South German brachycephaly is a part of the general racial problem of the Alpine highland region, and cannot be separated from a consideration of the same subject in Switzerland and Austria. Cranial collections from Bavaria, from Switzerland, and from the Tyrol all show the same characteristics in varying proportions. All are predominantly if not wholly brachycephalic, with cranial index means ranging from 82 to 86; all fall metrically into the moderate vault Alpine-Dinaric class, and all contain both planoccipital and curvoccipital skulls. There can be no other interpretation of this material, which covers several thousands of well-documented crania, than that they are the skulls of Alpines and of Dinarics, two variant brachycephalic racial types which formed the predominant population of the Alpine mountain system before the Germanic migrations and which have survived all invasions to which they have been subjected.

There is a decrease in blondism from north to south, culminating in the mountains of Bavaria where the hair is characteristically dark and the eyes mixed. From the distributional standpoint the most remarkable thing about Germany in a racial sense is the large head size typical of much of the country, and of the north and west in particular.

In other words, north Germans have the unbroken Cro-Magnid line, which came together from splintered sources, while south Germans have more in common with central and southern Europe. They also tend to be Catholic and have darker coloring.

To the mostly blonde and light-haired Anglo-Saxon population of England — descended from the same tribes that populate northern Germany — the southern Germans looked foreign and primitive, and also carried with them customs more like those of the less functional areas of Europe to the south and east.

This eventually caused the first American Nativist movement in the early 1800s:

Anti-immigration sentiments emerged in force starting in the 1830s, when U.S. citizens descended primarily from English and Scottish settlers bridled at the influx of Irish. Most of the arriving Irish were Catholic, prompting a hostile reaction among some Protestants that led to deadly riots in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts. The persistence of such prejudice made “No Irish Need Apply” one of the most iconic signs in the national memory.

The 1860s brought the Civil War and a desperate need for soldiers, leading to greater acceptance of new arrivals who were willing to join the Union Army. In the years that followed, some immigrants found acceptance as veterans, others made their way west to farm the interior or work in its burgeoning cities.

Toward the end of the 1800s, the flow of immigrants from Europe swelled again and changed in its origin. The new arrivals now hailed from Eastern and Southern Europe, as well as from countries that had been sending opportunity seekers across the Atlantic for generations.

The Nativists realized that the cities, where life was easy, drew the new immigrants, who were not pioneers coming to forge a land but people looking for an easier life than they had in old Europe, coming to take advantage of what the pioneers had made.

An old association of immigration and urbanization was renewed when the census of 1920 showed immigrants had helped shift the center of U.S. population from rural areas to cities and big towns.

That refusal lasted through four biennial election cycles, during which time Congress also passed an emergency ceiling on annual immigration levels and then lowered that by half again in the Immigration Act of 1924. That law set quotas by country of origin and explicitly preferred Northern Europeans over all others.

This gave rise to concerns of the political power of immigrant voting blocs:

In 1751 Benjamin Franklin warned that Pennsylvania was becoming “a Colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them and will never adopt our Language or Customs any more than they can acquire our Complexion.” Later Jefferson worried about immigrants from foreign monarchies who “will infuse into American legislation their spirit, warp and bias its direction, and render it a heterogeneous, incoherent, distracted mass.”

A self-proclaimed “city upon a hill,” a shining model to the world, requires a certain kind of people. But what kind? Do they have to be pure Anglo-Saxons, whatever that was, which is what many reformers at the turn of the last century believed, or could it include “inferior” Southern Italians, Greeks, Slavs, Jews, or Chinese of the 1800s, the “dirty Japs” of 1942, or the Central Americans of today?

The founding fathers opposed diversity and wrote a preference for “white” (meaning: Anglo-Saxon or other Nordic-derived ethnic Western Europeans) into the law the same year that they passed the Bill of Rights.

The flood of new migrants led to the rise of political machines, creating a pattern that would prove consistent not just for Southern, Mediterranean, and Eastern Europeans, but all minority groups because diversity pits minority interests against majority rights and creates massive corruption wherever diversity is tried, causing a steady migration toward Leftist (egalitarian) politics.

This political divide not only provided the impetus for the American Civil War, but also forced a re-alignment of political forces in order to address the chaos that diversity wrought upon the political system:

During the 1830s and 1840s Americans with nativist sentiments made a concerted effort to enter into the local and national political arenas. Nativism’s political relevance grew out of the increase of immigrants during the ‘20s and ‘30s and the anti-foreign writings that abounded during these decades. While pivoting between anti-foreign and anti-catholic appeals, nativism became both practical and ideological in nature: platforms for the movement ranged from extending the length naturalization to protecting the sacredness of the Protestant Republic. In New York city’s 1844 elections, the nativist movement formed the American Republican Party, which allied with the Whigs and resulted in the defeat of the Democratic Party. This political advancement, although local and short lived, presented a glimpse of the national nativist power later found in the know- nothings.

Much of this immigration began early in the life of the nation following the War of 1812, and led directly to the political machines, as chronicled Roger Daniels in his A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life (New York: HarperCollins, 1990, p.266):

In the years immediately after the War of 1812, capped as it was by Andrew Jackson’s glorious and seemingly providential victory at New Orleans, self-confidence — this period was sometimes called the Era of Good Feeling — characterized the national mood. During the war itself, Congress enacted a law prohibiting the naturalization of any Briton who had not formally declared the intention of becoming a citizen before the war started, but it was probably not effective and was repealed soon after hostilities ended. Encouragement of migration to the West and of immigration from Europe again became the order of the day. Congress did pass, in 1819, a law requiring that immigrants be enumerated at the various points of entry, but no bureaucracy was created to do the counting. That was left to Customs and other port officials. Naturalization proceeded rapidly, and many states, especially the newer western ones, gave immigrants the right to vote and hold office even before they became citizens. Legal alien suffrage, in fact, would continue at various places in the United States until 1926 when the last state to allow it, Arkansas, changed its laws. Many states treated the declaration of intention to become a citizen as if it were citizenship, and the whole process of naturalization was haphazard: Federal courts, state courts, territorial courts, and even justices of the peace issue certificates of citizenship or, sometimes, simply declared persons to be citizens. There was also much fraud in naturalization, most notoriously in New York City, where the Democratic political organization, Tammany Hall, would routinely arrange mass naturalization “ceremonies,” if they can be called that, before tame local judges, often in close proximity to election day.

The link between diversity, immigration, and votes against majority interest has been strong for longer than the Bible has been in existence and shows that tyrants like Tammany Hall encourage immigration in order to have a population that votes against the interests of the majority.

In the case of America, this population triggered a civil war, then took over politics, and now has opened the gates to the rest of the world, which is why American Nativism has emerged again as populism.

Tags: american populism, immigration, nativism, populism, tammany hall