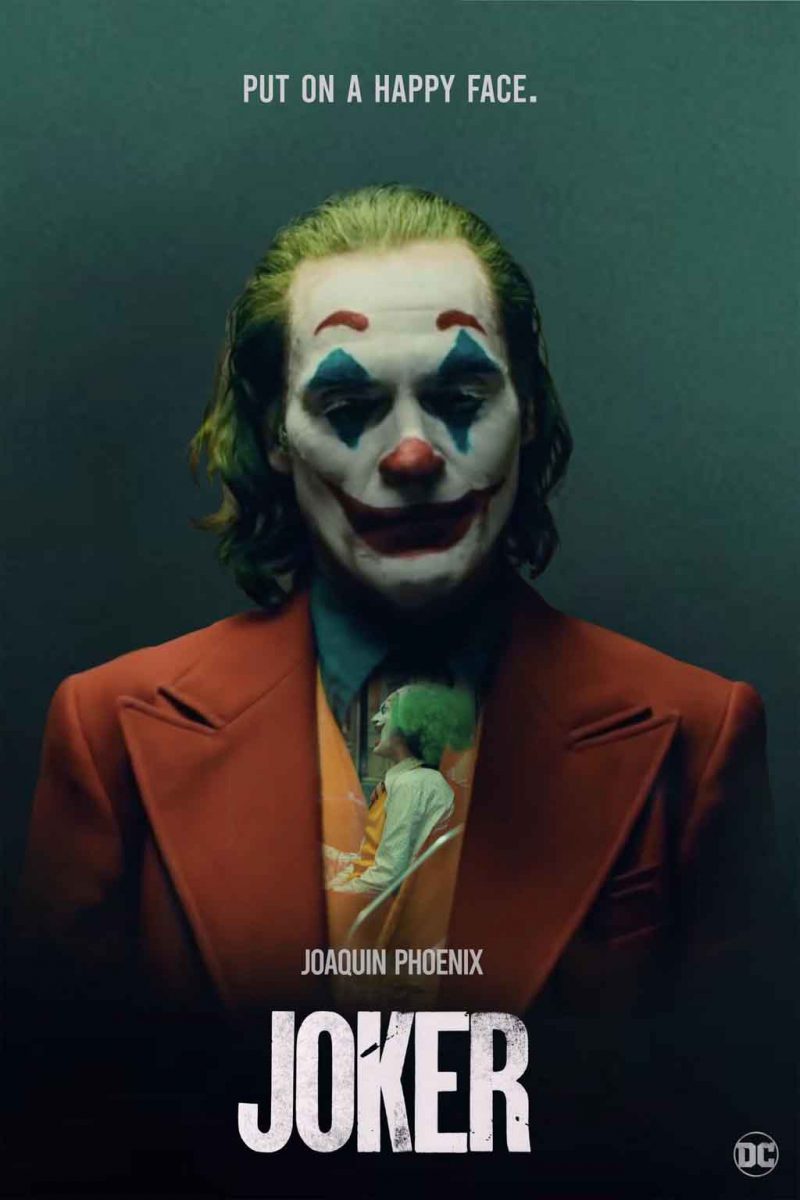

Joker (2019)

To understand this film, one needs a bit of context and even more patience. We live in a post-Revolution time, so all of our “cultural” works are pop culture, or those which glorify “the people” over the constraints of external reality.

This makes them both emotional and inward-facing, dealing more with the change in internal emotions than a change in psychological makeup such that we accept reality, maximize it, and embrace fate. These navel-gazing works, especially in the postmodern time, focus on the solipsistic individual.

To understand that, you have to look at a crowd as what happens when a group has no goal and instead, unites on the fact that everyone wants to be an individualist, or act only for their own pleasures (including power and status in the group), but have a gang to defend them for doing this.

Crowds form around the idea that everyone can be selfish and the group will defend them, and if anything goes wrong, someone else gets blamed, has to pay for it, and has to fix it. Understood as psychology, crowds are a brat tantrum of entirely narcissistic people unaware of the world outside themselves.

For this reason, most of our post-Revolution “art” and “culture” focuses on the French Revolution Narrative, which means stories where the people in power are there arbitrarily, and the misfits gang up on them and overthrow them, leading to a new Utopian age of tolerance and understanding, or at least, self-expression. Joker turns this on its ear.

At the expense of being ugly, the film focuses on a protagonist who is not an anti-hero but a non-hero. He does not sacrifice anything for something larger than himself, even an image or idea; he merely serves his own rage, frustration, self-pity, and deep sensation of inadequacy. He hates himself, and sees that hatred in the world, so he visualizes only the negative and hates the world, too.

Those drawn to him come from the Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris, Elliott Rodger, John Hinckley, and Gavrilo Prinzip school of self-destruction paired with the ruination of everything that could have been something better, or could be something better in the future. This is Ahab going down with his ship rather than having been proven wrong, Suaron collapsing into dust, and Judas hanging himself from a tree. There is no victory here, especially in victory for the main character.

Filmed in what we might call a gritty art deco, like a hybrid of the 1920s and 1990s, the movie features bright colors and bleak, washed-out 1970s cityscapes, combining New York and Chicago into the ugly mechanical churn of Gotham City. In the Batman mythos, Gotham is always ugly, but in this case it has dominated the character (Arthur Fleck) who becomes the Joker: he has invited the ugliness into his soul by being focused on his own suffering.

This makes Joker the inverse of Batman, a Christ-figure, in that Bruce Wayne decides to descend back into the abyss of Gotham in order to save it, while the Joker descends below the abyss of Gotham in order to harm it. One does not find villains this perfect in real life, driven by only an impulse to destroy, until one gets to the Manson Family, Son of Sam, and Antifa. His pathos finds a comrade in Gotham and makes love to the ugliness so that it can beget nothing, but by having mocked the life-impulse and ended with barrenness, can exclude any possibility of anything good.

An atmosphere film punctuated by periodic chaotic violence, Joker shows us the psychology of the French Revolution as we rarely see it laid out in this time. In doing so, it is a song of revenge on our civilization. There is no transcendence here because there is no will to transcend in that which denies external order, then blames it for the lack of itself, and then substitutes human self-pity and pathos for the stable world that it wishes it has.

Joker emphasizes that constant inversion by showing us the ugly city in parallel to the soul, specifically that which attempts to be 1970s colorful but has faded, as contrasted with the Joker who talks constantly about his happiness yet never actually seeks joy. This is the Columbine massacre more than incels, but shares a commonality with them: it believes that nothing is good, and nothing good can come from this world, in any interpretation of “good.”

Like most atmospheric films — these have been popular since the late twenty-teens and remain so — it builds slowly to a short, intense and inevitable conclusion, and in doing so, nicely flips outward the inner drive of this character, mirroring our own fond images of civil rights, revolutions, and people power as the gross animal selfishness that they are.

Few of us would opt to see this film again unless we prize ugliness. No, this is punk rock disguised as an art film camouflaged as a superhero epic; it aims to beat us like the Joker would, shoot us in the cafeteria like Brenda Spencer, or rage-quit like Thrasymachus. It wants us to slowly immerse ourselves in a disgusting character, sympathize with him, and then see where such sympathies lead.

Consequently, it runs a bit long and, no offense to the undoubtedly talented filmmakers and actors, boring. Its only structural flaw is that Joker needs to be more like Jim Morrison, whose stage dances the protagonist mimics, and show us the enigmatic side of this ugly life. Revolutions are not stupid because they are ugly, but because like all really dangerous deceptions, they seem beautiful until the flower opens and we see the infinite blackness within as it swallows us whole.

Tags: batman, french revolution narrative, joaquin phoenix, joker, movie