Nihilism, Universalism, Conservatism

You might wonder to yourself, what kind of a person would attempt to pitch nihilism to conservatives, and what might they hope to gain?

Understanding this quixotic pursuit requires us to look into the invisible world of philosophy, where instead of comparing good/bad categories, we inspect the structure of ideas and how they related to reality. Nihilism might be described as ultra-realism, or a rejection of human emotions, judgments, feelings, and desires in favor of what we can discern about the world out there.

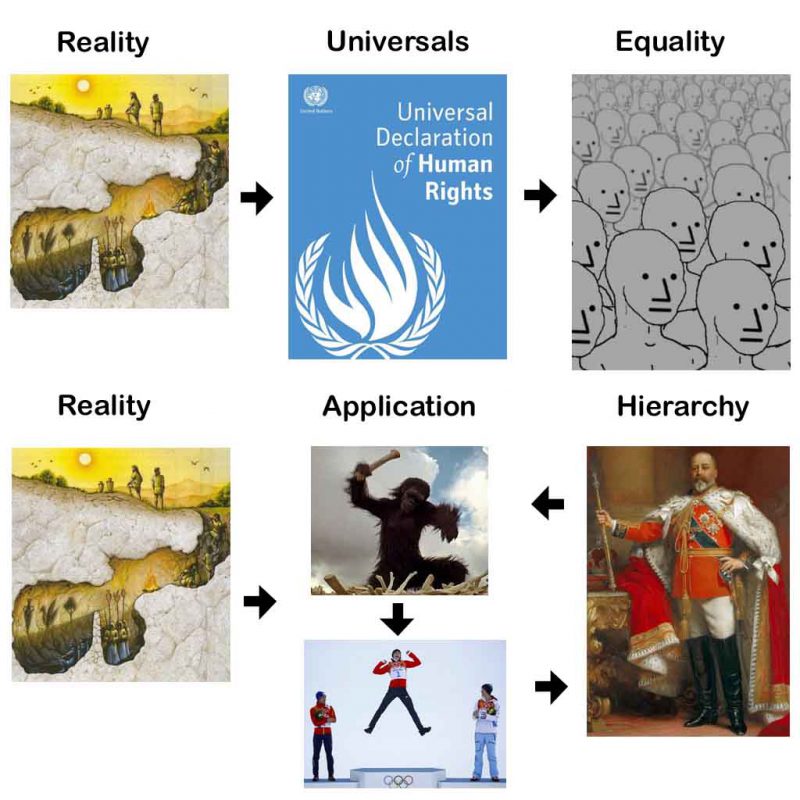

The image above offers us examples of nihilism and its opposite. In the first row, we see humanism and related philosophies like egalitarianism: we observe reality, come up with a rule that we think that all people can follow, and from that create a population of equals who are controlled directly to enforce their obedience to the rule.

In the second row, observation of reality initiates a cycle where individuals attempt to apply their knowledge of reality, and then a two-way process occurs where those with the best results rise in a hierarchy, while those who produce lesser results — even if they already have a position in the hierarchy — find themselves demoted.

Equality requires control. Instead of seeing results in application, and taking the best according to that and rewarding others for doing what they did, equality acts before results can be measured — an anti-accountability action — and instead sets up a conjectural best practice which is enforced on everyone so that no hierarchy can emerge.

In this way, equality works as a type of centralization because instead of delegation, you have a central command which tells everyone what to do as a mass, which means that it gets no feedback from the person on the ground and operates blindly, using blocky generalizations and rules instead of understanding of the details of the task at hand.

With equality, we never find out who people are “inside.” They are forced to do what the central authority wants, and never make any decisions of their own, so their moral and intellectual differences remain hidden. This benefits their controllers, who simply want to use them as tools to achieve the goal of control, which mainly consists of perpetuating itself.

Nihilism states that there are no universal values, truths, or communications. Instead of claiming that all values, truths, and communications are equally correct, this claims the opposite, namely that nothing is equally or universally correct. These things depend upon our ability to perceive them, and someone with an IQ of 70 will see a different world than someone with a 140 IQ.

Even more importantly, our inner traits regulate what we see. Some people are more interested in the structure and workings of the outside world, and so notice more, just like some who are more tuned to biology notice more of nature. What they see cannot be directly communicated to others, just like advanced math cannot be taught to those without the intelligence to see it.

We see this with human cognition through the Dunning-Kruger effect: to people without enough raw intelligence to understand something, not only does it come across as bizarre nonsense, but they unreasonably assume that they know better, simply because they lack the circuits to see where they are incorrect.

Universal truths require everyone in the room to be able to understand things as true, valuable, or from the tokens of language and picture that we use to communicate. Since perceptual abilities differ, not everyone can understand, which means that instead we have a hierarchy of understanding, with some knowing more — and knowing better — than others.

This clashes with the classical modern view of the world, which holds that not only is there an objective reality but an objective truth including a values system. This, the moderns reasoned, could be encoded in rational logic and conveyed through symbols, and soon everyone would equally understand the same view of the world.

Our modern systems rely on this notion. We set up capitalism, assuming that the audience will act in self-interest which they can perceive roughly equally; we create Constitutions and laws, figuring that whoever reads those words will understand them in equal replication of our understanding.

We assume that what we perceive as true and the root of our values can be communicated to other cultures, whether among us or at home in their native lands, creating the basis for a single international set of values and behaviors. The more people we get into this group, we reason, the more stability we create and the safer we are from those who deviate from those values.

In reality, we are merely projecting because of our fear. We want the world to operate as it does in our minds, and so we hope to rope in others to see it as we do, making that more like a god guiding reality to be as we see it than something specific to us. We hope to conquer loneliness that way, and have others become “reasonable” to our perceptions and needs.

Our solipsism has us insist that the world can see itself the way we see it and therefore, can be controlled in the way that we hope. This control mechanism relies on the notion of absolute, universal, and objective truths, values, and communications; in reality, those do not exist because of the inequality of human beings, including moral inequality where some care more about what is actual than others.

Conservatives in particular suffer from this dysfunction. They want to set up a truth, like economics or a Bible, and enforce it on everyone else so that disorder, strife, non-conformity, and chaos can be eliminated, but in reality, only the people who are like them can understand most of what they see and appreciate the value in it.

The grim reality appears to be, however, that people can only understand what fits them and where they are in the hierarchy of human beings. We can enforce rules on them, but when left up to their own devices, they will re-interpret our rules, just like our religions, laws, art, architecture, and technology. Only we can do what we do.

This means that instead of looking for universal truths that we can use to control others, we need to look for the best among us and give them power, so that they can use their greater ability to perceive to make more accurate assessments of reality and act on them.

Tags: conservatism, nihilism, universalism