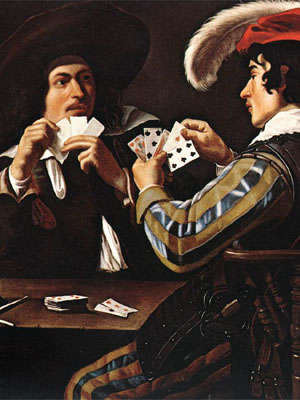

Hearts

Last night I played the card game Hearts with friends. Hearts is an evasion game based on “tricks,” or turns in which a cards are played, and whoever loses “takes the trick”: they must take the cards that were played and adds their number to his score. You do not want points.

Last night I played the card game Hearts with friends. Hearts is an evasion game based on “tricks,” or turns in which a cards are played, and whoever loses “takes the trick”: they must take the cards that were played and adds their number to his score. You do not want points.

Every Heart is worth one point, and the Queen of Spades is worth 13 points. The highest card played, of the suit led, takes all the cards. If no one can follow suit, then the person who led must take the trick. You must follow suit if you can, there is no such thing as trump and card rank is precisely as you would assume; Ace is highest, 2 is lowest.

The most basic strategy is to short suit yourself as quickly as possible so that you cannot follow suit. That way you can get rid of your high cards and start laying your Hearts on tricks. So if you have no Diamonds, and a Diamond is led, you are then free to lay whatever card you want on that trick. The object is to have a low score, not a high score.

I found myself in this situation: I have the Queen of Spades and two lesser Spades, I know who has the Ace and King of Spades, and I know that she knows that I have the Queen of Spades. Because I know there are 13 Spades in total, I may as well assume that she also has at least one other, lesser, Spade, and that the other two opponents have three or four Spades, as well.

As the hand played out, I had a decision to make, to lead the Queen of Spades or not. Leading the Queen is a really risky move and you almost never want to do it. The more common strategy is to try to lay it off when you don’t have to follow suit. I was in a bold mood, however, and I was dying to try this gambit out. I knew if it worked it would become the stuff of legend.

The gal with the Ace and King had already played a lesser Spade; I had to get rid of this nasty Queen of Spades at some point, and at some point she was going to get rid of the Ace and King as well. I was not short suited and this all added up to a precarious situation. So I lead the Queen, hoping she would have no choice but to follow suit with her Ace or King and take it.

By golly, she had the Jack of Spades and I had to eat that darn Queen! It was a backfire but there are some great lessons here.

In this specific instance it turned out to be the wrong play. But all things considered, the percentages were not entirely out of my favor given the already precarious situation I was in. A lesser card player and gambler might say to themselves: well, I’m never going to do that again!

But that would be somewhat mistaken, because they are taking that specific instance to trump what are unarguable percentages – there are only 13 Spades total, and only two Spades that can take the Queen. It was not necessarily a bad play considering I only had so much information and one must essentially assume that all players have 3.25 Spades in their hands.

I had some information, but not all. I used logic that everyone basically had three Spades in their hand. The Queen had to be played at some point, the Ace and King had to be played at some point. A decision has to be made and a risk has to be taken.

Specifics are actually more misleading than generalities. This is precisely why there is such a thing as professional poker players. They play according to the percentages; they shake off the bad beats and live to fight another day. In the long run, they gain the edge.

The same applies to a good many situations in our modern world. Most people want you to believe the exception disproves the rule, which suits them since they want to believe they’re unique sui generis precious snowflakes. Taken with the percentages, however, the exception proves the rule, and it is how in the long run we can win.