Bem

“That’s not his name,” spoken softly, divided the hardware store immediately. Janus went back to the storeroom. Marc snickered, and Dalwood Higgins, the proprietor, shot him the usual dirty look. Across the street, construction resumed on what would eventually be a competitor for the centuries-old hardware store, a new chain outlet made possible by the decadal growth of Westford into a big small town.

It was a Wednesday morning, bright and blue but slightly humid, so everyone was moving slowly. The object of the discussion waddled out into the main room, eyes not quite tracking anything but the sides of his path, and presented Higgins with a board. “Not quite, Ben,” he said with an airy and gentle voice. “We need two thirty-two inchers, and this is a twenty-two.” The co-owner, Jacob Merriweather, looked on for a moment before returning to the figures he had propped up on a stack of paint cans ready for the spring construction boom.

“Oh no. Okay, I will go back to cut another. I will be right back,” said the round-headed figure, who then ambled back toward the storeroom taking the route he had taken.

“Watch this,” Marc said to Jon Hughes, the one of the “boys” — workers who did everything from janitorial through construction advice in this egalitarian and friendly workplace — paired with Marc for the day.

“Hey, who’s there?” he called out.

“Bem!” said the round-headed one, resuming his shuffle toward the back of the store.

“We shouldn’t have to call him ‘Ben’ when he can’t even pronounce it,” Marc said to the room, and idled off to the back.

Merriweather stepped over toward the cashier area where Higgins was minding the store. “He’s not doing so well,” he said. “We have to pretty much triple-check anything he does.”

Higgins pushed his glasses back on his face. A thin man with a moustache, he inherited the store from his grandfather after his father chased the Grateful Dead into an overdose grave in Canada. “Ask around,” he said. “Everyone in town, all the old families, think that it’s great we have them here. Ben is only the second one we have tried, and it gets them out of the Facility so they can have normal lives. It really helps our public image.”

“Do we need to fix that?” said Merriweather. “We sell wood, paint, fixtures, and gear. No one cares.”

“Yeah? Well, who do you think is going to go to that new chain store if this store has been here for centuries and supports the community, especially its most vulnerable?”

Merriweather just raised an eyebrow. Having co-owned the store since the last world war, his family had a vested interest in it, but lately conversations with his father had steered his interest more to real estate and home-building to capture the steady flow of people from the cities on both sides of the mountain range. They came fleeing something, an indefinable corruption, that afflicted the cities as if it disrupted their thinking. Demons, he wondered, or just the usual seven sins?

Most of the workers here came from the adrift among the founding stock of the town. If you lost your way in life, sober up and get a job at Higgins Hardware, went the prevailing wisdom. Marc showed up after his second DUI, Janus had dropped out of college, and Jon had moved up from the basement of his mother’s home after she met a man from Reno and moved out suddenly in the night. Merriweather knew Higgins saw his store as a pillar of the community for this, but he also knew that Higgins had been an art student before getting called back to run the desk.

“All done!” Bem brought out two more boards, visually identifiable as being different lengths, while Marc chuckled and Merriweather rolled his eyes.

“Thank you, Ben,” said Higgins. “Can you check the compactor?”

“Rokai!” said Ben and happily trotted off to the rear of the store. Even Higgins knew that customers sometimes flinched when they looked into the empty but wandering eyes of his mentally retarded employee.

Janus walked over to Higgins and took the boards. “Thirty-two inchers?”

“Two,” said Higgins. The wrong boards went into the scrap pile, and Janus went back to the cutting station. The customer had now been waiting for a half hour and left without a word after paying when Janus brought the boards out five minutes later.

“Ain’t gonna end well,” Marc said, taking a broom to the back alley.

Spring has a way of making one forget cares however. The customer turned up the radio on his drive home and sang along, soon distancing the board fiasco from his mind. The workers did their best to get outside, in the breezy air and warm sun and chirping of cheerful birds. Higgins went over the figures Merriweather presented, and together they decided that paint was going on sale tomorrow.

And so it went, for several days. The weekend was just a few hours away, and Jon had just sold four cans of custom paint, feeling pretty good about his first successful act as a salesman. He carefully mixed the different colors in four cans he set on the counter, then lidded. I could do this, he thought. I like people. But I still need Marc to run the paint machine.

As Jon walked to the east side of the store where Marc was stocking pipe fittings in the wire mesh baskets, bent from straight sides into something resembling pouches, Ben darted forward to the paint station.

“Ben, we might want to wait for Marc, who’s the guy who knows that,” said Janus quietly.

“Cans go on the bars. Bars go around. Ben fix,” said the blank face. Janus quietly picked up the broom and headed straight to the sidewalk, keeping it clear as a community service as Higgins had long instructed him. Almost no one gets in trouble for that.

Jon came back with Marc. “OK, you’ve got the cans on the bars. Now you just want to set the frequency and duration, here, then press ‘start,'” he said, even as Jon was looking over the order.

“Wait,” he was starting to say, having noticed that the mixture seems wrong, but he couldn’t get the words out in time before Marc mashed the button.

With a thick pluppfing sound, the cans exploded as the machine began its two-vector agitation. Paint covered the floor and two nearby displays. “What the hell?” Marc said, yanking the emergency stop.

“It’s the wrong paint,” said Jon. “I didn’t load these, but I was checking the sheet” — he gestured at the now paint-covered clipboard — “and these aren’t even the right cans.”

“Two of these were waiting for a pickup, already mixed. The lids aren’t malletted,” he said, continuing his investigation.

“Who put the cans on the machine?” said Higgins.

Both men looked at each other. “And didn’t you put on the safety bars?” asked Higgins.

“They broke a week ago,” said Marc. “Ben tried to oil them with WD-40 and they slipped the chains. We’re waiting on replacements. Did Bem put the cans on the rack?”

“Ben,” corrected Higgins. “I don’t know. But you should have checked the bars. You guys clean this up, and I’ll make this mix with the old machine in the back.” No one liked the 1950s-era mixer, since it was prone to violence and noise. He took the paint-smeared document, slicked off some paint with a finger, and looked around for a towel. Shrugging, he whipped it off his hand onto the floor, which was already covered in paint.

It took late into Friday evening for the two to clean the fast-drying paint, and by the time Marc made it to a party his new hope for a best girl was already making out with the flabby former quarterback, the beer was mostly gone, and his crew had already cut out to go to the real party, which per convention was not discussed since they didn’t want the drips from the open party going there and washing out the conversation.

Jon went home to his wife Marcy. She didn’t cook, so dinner was late for all of them as he boiled some pasta and added sliced chicken, red bell peppers, garlic, and green onion. Feeling a bit tired, he tossed in some of the Cantonese hot sauce he had acquired at the local international market, but this made it too hot for the baby so he found himself pureeing carrots and zucchini instead while everyone else ate. He took his plate to the sofa and turned on the television. Marcy joined him later, but conversation was scant and he went to bed early.

Merriweather drove the long way back to his bachelor pad, the antique family home, where he enjoyed — a euphemism that amused him — a dinner of microwaved spam. Tomorrow was visiting day, and his former wife would be arriving from Denver with the kids who now treated him like an alien, perhaps with her also-ran soap opera boyfriend in tow. He watched an old John Wayne flick, so timeworn in this house that he could finish the lines of dialogue when the DVD player glitched, and then turned in early on the sofa, awaiting the dawn.

Janus stocked paint in the window, knowing that Higgins would appreciate his attention to detail. Having seen enough of life to know that he trusted his own thoughts while pushing the broom more than what he found in others, Janus spent his time mostly alone and pursued a policy of neutral non-intervention whenever possible. Part of this reflected his good nature, but half of it came from his dark side, which enjoyed watching fools follow their foolish pursuits and be destroyed for it. Like America itself, the countryside had an easygoing “vibe” which was equal parts benevolence and natural selection.

Marc nudged him while they were locking the glass case behind which the display sat. “Chain hardware across the street is taking applications,” he said. “They’re going to bump me up a level to assistant paint station wizard,” he murmured.

Janus puzzled over the strange new, city-sounding title. “And you’re telling me this out of the goodness of your heart?” he asked.

“Referer bonus,” said Marc, laughing. “But even more, it’s time to get out of a sinking ship. They buy ten times what we do and sell at half-markup. It’s going to be a gold rush over there.”

“Higgins says the community will support us,” said Janus absent-mindedly.

“No one pays more for a nice guy,” said Marc. “If Higgins knew, he’d be cutting prices now, and getting rid of the tard.”

“It can’t be all that bad,” said Janus. “Bem does okay, sometimes.”

“Rokai,” said Markus, crooking his arm. “Find a customer who wants to wait a half-hour for a five-minute job just to support the retarded. Most of them are probably thinking now that Hitler didn’t go far enough in snuffing them. You know he gassed tards first?”

“No one gives a shit,” said Janus suddenly, surprised at his vicious tone. “Hitler also worshiped Satan, the angel who rejected working with others so he could rule a trash-heap in Hell.”

“Whoah, even the nicest guy on the block is getting salty,” said Marc. “It’s okay, bro, just think about the offer.”

At that moment Higgins came out. “Can you guys help Ben out front? He’s trying to load a new mower for Mr. Davies, and he needs some aid.”

“Well, that went well,” laughed Marcus, holding the bloody rag over his foot.

“Keep it still,” said Janus. “The doc’ll be here any moment.” Ben had misunderstood an instruction to keep the boards that they were using to roll the riding mower into a pickup truck, and at a crucial point, had moved a board, causing the mower to tip over onto Marc, dragging Janus over the boards. His arms were covered in welts and scratches.

“I look like a murderer,” he joked. “She fought back.”

“Ah, they’ll never find that shallow grave!” said Marc, and for a moment, the two were laughing like old times, pre-Ben lazy days at the hardware store.

“They never do, out in the hills that are a thousand times the size of this town,” Janus said thoughtfully.

“Not in a thousand centuries,” said Marc. “Wonder if Ben will wander out there some day and get eaten by bears.”

“Even the bears don’t have that kind of patience,” said Janus, surprised at his own cruelty. They laughed together like old times.

When the doctor left, Marc had a new compression cast fitted to his ankle and some pain pills. Using a footstool, Janus was able to hold up the display case door long enough to get the glass in and lock it.

He turned around to look accidentally directly into the grey-blue eyes of Higgins. “I need you in back,” he said. “Ben tried to do a plywood order, and we need a re-do. Rush job,” he added.

That week was hard. No one had liked their weekends, mainly because on beautiful days people live in the sunlight and do nothing exciting after hours, so if your weekend consists of socializing or going out, it tends to be boring. And yet, everyone was tired, something about a norther bringing in pollen from the yucca and oleander that makes everyone logy, tractable, and complacent.

At this point, a pattern was established. Customers would arrive, and at some point, jobs would be handed to Ben. Some of them he did well, if they were simple. Others became several jobs in themselves as he was re-instructed, re-directed, and sent back re-do them, with oversight by Merriweather or Higgins, while the customer waited, probably wondering why this short errand had become such a disaster.

The church ladies came in to talk to Higgins and afterwards, he was doubly sure about how Ben was a huge success. Ben got paid the same as anyone else in the store, although he was permanently at entry level, and Higgins thought they should acquire another mentally challenged youngster from the Facility up on the hill. The church ladies were delighted. Westford truly stood behing Higgins Hardware! Merriweather started as if to say something, but went back to his office, probably looking again at real estate, as he seemed to do a lot these days. The chain hardware store construction was completed, and stocking had begun. Marc gave his notice and Higgins did not seem to mind.

Jon and Janus found themselves on compactor duty. This required piling up all of the boxes and packaging material which had come with the morning shipment, something Marc and Merriweather normally unpacked in the early morning hours. A large metal funnel channeled all of the junk into a pressing chamber which reduced it to untidy blocks of mashed cardboard, styrofoam, cellophane, and paper. Then Bem trotted the stuff out to the dumpster on a little cart, and the day could go on.

“Careful,” said Janus, holding Jon back. “The chain is loose.” The chain kept an operator from sliding on the unstable platform above the hopper and potentially falling into the crushing chamber. Something had yanked it where it was connected to the far side of the platform, so now it could slip from the opposite side to where the clip attached, the location one would expect. “We’ve needed this fixed for weeks.”

“Bem got it caught in that big refrigerator box a month ago,” said Jon. “Yanked it right loose from the metal. Marc tried to fix it with pliers, but it’s too tough. We need someone in here with a clamp to mash it back into shape.”

“His name is –” began Janus, but then he stopped. He realized in that moment that he was leaving this job. He took it because he could do it on autopilot, leaving him alone with his thoughts and a lot of free time as he wandered the store, lot, alley, storeroom, and sidewalk. But something about this whole thing felt like the hopper, a bunch of empty used-up forms sliding into something which would remove all of their shape.

“Well, that takes care of it for today,” said Jon, oblivious to the consternation next to him. “I love working here,” he said suddenly. “You’ll never find a place this relaxed at that chain hardware place, or anywhere else. It’s a real family business, and maybe someday I’ll be floor manager.” He walked off quickly, almost angrily.

“Someday, we’ll all be dead,” said Janus to no one.

They left on Friday evening with a sense of things being incomplete. Bem took a customer order, got two numbers backward, and so Jon and Merriweather spent the afternoon driving back and forth to fix it. Higgins got a cold and spent the time huddled in his office. The chain store put up a sign promising an opening soon.

Jon spent most of the weekend in his garage pursuing his hobby of making miniature chess sets. Using a magnifying glass, turning lathe, and an assorted of knives imported from Switzerland and Japan, he created tiny chess kits which he lovingly photographed to post online. He could not actually play chess but viewed this as academic. His wife spent most of the time on the phone, and asked him to get wine coolers at the store.

Janus set up his tent on the river shore. He felt loneliness, but dismissed it much as he did the perpetual taint of headache that now followed him on the job. He thought it was from the paint fumes; it was gone now. With a few books, a fishing pole, and his trusty one-hitter, he spent an enjoyable weekend but made conversation until it became awkward with the deputy at the trailhead when he bolted out Monday morning to grab a shower and straggle in to work early.

Merriweather told no one what he did, becoming like a stealth bomber flying high over the Adriatic Sea, both reflecting no signals and emitting none of his own. Some say his career as the Baron of the Valley, the real estate developer who specialized in making the right offer at the right time to farmers with great overlooks and building condominiums that the goats, sheep, and cows would have found obstructed their access to the sweetest of dew-fed hill grass.

Marc hung out and drank, rather angrily. He thought that the chain store would be a new opportunity, but after a girl repeated back to him that he was simply moving across the street to do the same stuff for more money, he fumed all weekend. On Sunday afternoon he left a message to his lawyer about investigating how he could get his record sealed, so that he did not have to be a glorified stockboy forever.

No one, least of all Bem, knew what Bem did. His mother was able to run him up to the Facility for “activity time” on Sunday afternoon, and she got unsteadily drunk afterwards and set off the smoke alarm making toast. Her husband tucked her in and then, like her, dropped into a sleep without dreams so much as recollections of a warmer time, when he felt young and they had time for each other.

Monday dawned bright and warm, so Merriweather hurried through unpacking the deliveries for stocking. Marc helped, sort of, but as he was obviously hung over, Merriweather just bulled ahead and did the job, then raced into his office to peremptorily dismiss paperwork, emails, and phone calls. Then he went out onto the floor, took out his inventory checklist, and proceeded to stare into the distance for several hours.

Perhaps still thinking that he was at activity time, Bem happily prattled through a half-dozen wrong orders, spilled a gross of nails, jammed the phone lines by leaving the buttons engaged, and “cleaned” the floor in the storeroom with so much water that Janus went flying when he rounded the corner.

“Careful there,” said Higgins. “Safety first.” His cold was gone but his eyes remained watery and wary. He frequently went to the sidewalk to watch the chain store rising, as inexorable as the sun ascending the sky only to disappear, leaving all of us in the dark.

Jon, Marc, and Janus fixed up all the Bem errors, then got told absently by Merriweather that they still had to do their regular duties, too. It would a hustle to get everything done by five. “Last day?” asked Janus.

“Tomorrow,” said Marc.

“We’ll miss you,” said Jon, because that was the right thing to say, and in the profile in his mind of the successful businessman he wanted to become, that was what this person would say. His thoughts dissolved as he remembered that he had been unable to get through to his wife all day, getting a busy signal.

“Closing time,” said Higgins. “We just got to get the compactor and — wait, where’s Janus?”

They saw him far off, sweeping the very edge of the lot with great gusto, as if he had discovered something vital to the protection of the business.

Bem wandered off.

Merriweather watched Janus. He was now whacking away at weeds with a fury. Then Merriweather looked down at the paperwork he had been reading all day, realizing that he remembered none of it, recognizing that this would not matter, and also that he did not care, at all.

They were just about done when Sheriff Johnstone walked in the front. “Evening folks,” he said. “Lady passing by mentioned that she saw something like blood leaking out the back of the place.”

“Must be paint,” said Marc. “Another Bem incident.” He wondered how late he would be to that night’s open mike session after cleaning up this one, and realized simultaneously that he would not make it in time to go home, get his guitar, and get a slot, and also that he did not care.

Higgins slid off his stool, nervously whisked hands over his face, and went into the back. Only seconds later he appeared with a face whiter than the new paint they sold for the condos that reflected enough light to make the long, dark tunnels — basically glorified trailers — seem light and open enough for the photographer to capture so that they could be sold, and who cares what happens after that.

“It’s Bem,” he said. “He — the compactor — the chain — water and oil — oh God I have to tell his mother,” he said.

He need not have worried. When she put the phone down, she went under the sink and dug out the wine coolers she kept hidden in the old toolbox. By the time her husband came home to ask if she had heard, she was stone drunk and staring into space. He closed the kitchen door and went to the garage, since he had to rebuild a disposal which had gone bad at their rental property across town.

Johnstone took depositions from them all. “Looks like there was some water dripped onto that platform,” he read from his notes. “Some oil there too, looks recent. Kid just slipped, chain snapped back, and he fell into the hopper. No one heard any screams?”

He looked up to see dead eyes. He flipped the notebook closed. “Tragic accident,” he said.

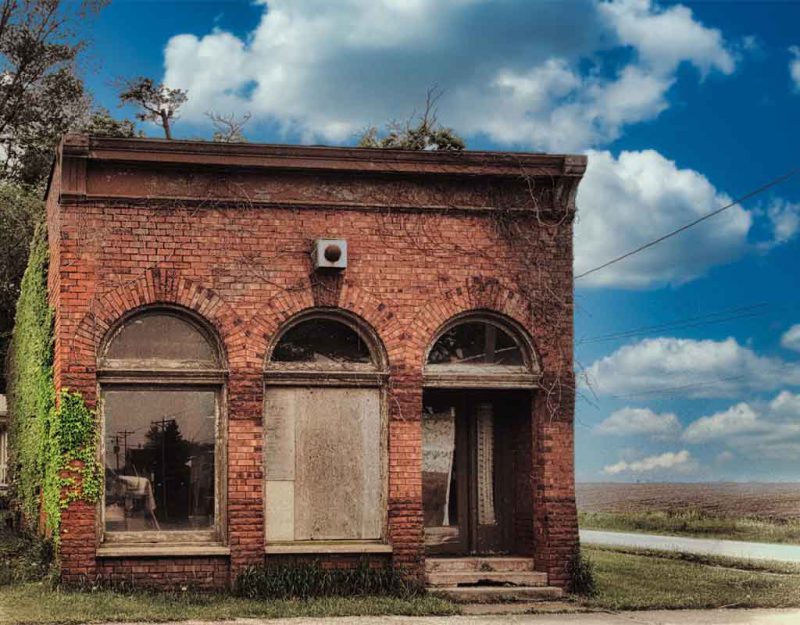

Those words reverberated around town, when the next morning Marc was wearing the skyblue apron of a chain hardware store. They whispered through the leaves when Merriweather took a buyout and disappeared into the hills with his construction crew. They echoed down the alleys when Higgins Hardware went bankrupt and was renovated into another high-rise of trendy condominiums.

Janus looked up from his new job at the coffee store. Business was slow. He liked the hardware store better, except for the crisis that had come up. He took a broom to the street, giving an air of life to the quiet store selling coffees for half of what he earned per hour.

In his car, Jon sung along to the radio. It turned out that Marcy preferred the attentions of her yoga instructor, and they wanted the child, the house, and him to clear out. Feeling very smugly competent, Jon send out some resumes and got a hit — a big hit — in Los Angeles, where they like to hire innocents from the hills to work them until they are used up. He knew now that he would keep this for only as long as he needed it, then move up. He really didn’t care, anymore, if he ever did. It was all about the moment. He turned up the radio to block out the rushing wind noise of the last of the mountains.

Marc liked his new title and pay rate, but discovered to his horror that team bonding missions were not just not something the movies invented, but his job to run. Soon he became accustomed to the plastic smile, contextless platitudes, and endless patience of the customer service worker. Sometimes he wonders how Bem died, and remembers that Merriweather had an oil can and Janus an iced drink, something he almost never consumed, on the day in question. But these were coincidental, surely. He also remembers loosening the chain a bit further with the multi-tool he kept in his pocket, and that he saw Jon push the hopper closer to the platform. But these were circumstantial. Maybe we all did it, he thought. Maybe the hills did. Certainly no one wept over Higgins Hardware, least of all the church ladies, or Bem, least of all his parents.

Janus stumbled out of his reverie. The boss man, the great-grandson of a once prosperous ranching family back from his engineering degree in San Jose, pointed to the sidewalk. “Still dirty,” he said. “Do it again. The customers are coming, soon. Ad campaign hits tomorrow.”

“Rokai,” said Janus.

Tags: eugenics, fiction, retardation