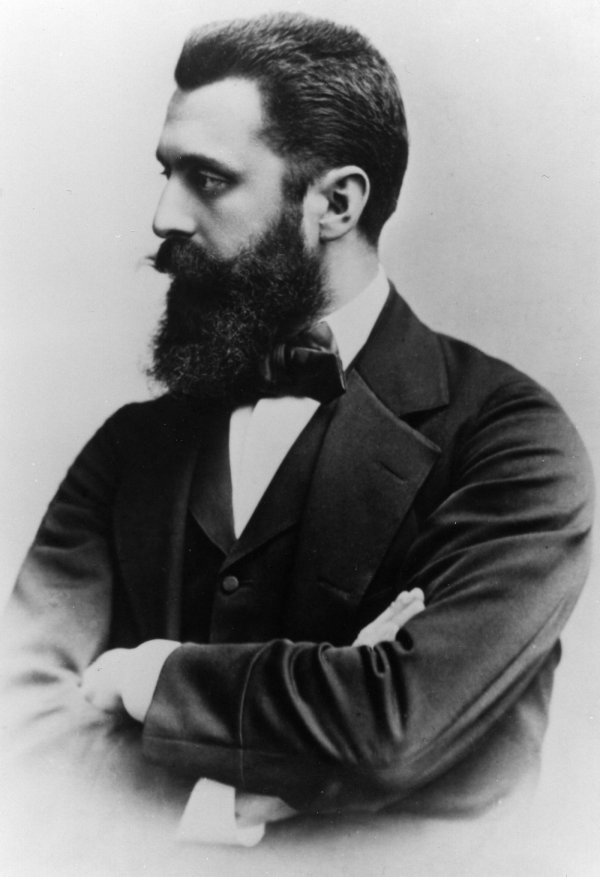

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl (1860 – 1904) was first a lawyer, then a journalist, and finally, a political leader. It was as if the blindness of the law inspired him to notice conditions in his world, and eventually, to apply the skills of lawmaking to create situations where such conditions did not arise.

Born in Budapest to a German-speaking family from Serbia, he moved with his family to Vienna at age 18, eventually getting a law degree from the University of Vienna. After less than a year of working in law, Herzl became a journalist and writer, gaining most renown as a correspondent and later literary editor for the Neue Freie Presse in Paris.

Although he came from a secular background, and was educated in the spirit of German-Jewish Enlightenment of the period, his grandfather had been a friend of Rabbi Yehudah Alkalai, a proto-Zionist of an earlier generation. As a young adult, Herzl worked for a Burschenschaft association, which strove for German unity under the motto Ehre, Freiheit, Vaterland (“Honor, Freedom, Fatherland”), and was an avowed atheist.

With the eye of a journalist, he considered the “Jewish problem” a social issue like any other, and wrote an early play, The Ghetto (1894), which rejected assimilation and conversion as solutions for the Jewish people. The following year, his opinions changed when he heard a crowd shouting “Death to the Jews!” in the aftermath of the Dreyfuss Affair, in which a French-Jewish military officer was accused of treason. This changed his outlook from one of Jewish independence to one of Jewish nationalism.

In June of that year, he wrote in his diary: “In Paris, as I have said, I achieved a freer attitude toward anti-Semitism… Above all, I recognized the emptiness and futility of trying to ‘combat’ anti-Semitism.” He came to consider the idea of Jewish sovereignty as a political response to what he saw as an international political problem, which was a lack of national identity for the Jewish people causing them to be perceived as enemies of other nations, and saw the solution as the creation of a Jewish state with the consent of the great powers.

As a result, in 1896 he published Der Judenstaat, a pamphlet-length work in which he argued for the creation of a Jewish state. Der Judenstaat was a title that punned on the Judenstrasse of medieval times, which was a street or ghetto to which Jews were relegated.

In Der Judenstaat he wrote:

“The Jewish question persists wherever Jews live in appreciable numbers. Wherever it does not exist, it is brought in together with Jewish immigrants. We are naturally drawn into those places where we are not persecuted, and our appearance there gives rise to persecution. This is the case, and will inevitably be so, everywhere, even in highly civilised countries—see, for instance, France—so long as the Jewish question is not solved on the political level. The unfortunate Jews are now carrying the seeds of anti-Semitism into England; they have already introduced it into America.”

Herzl believed that Jews could never assimilate, as the majority in each nation-state determined who was native, and by exclusion, Jews would be seen as alien. To end this permanent outsider status for world Jewry, he proposed that Jews have a nation of their own, to the benefit of Jews and Gentiles alike. His vision of this state corresponded to the modern pluralistic, tolerant democracy, which he described in a later novel, Altneuland (“Old New Land”) published in 1902, which depicted a Jewish social utopia in Palestine.

Although he did not live to see his vision completed, he was able to create the First Zionist Congress in Basle, Switzerland in 1897 and from the forces there joined, found numerous Zionist organizations: the newspaper Die Welt, the Jewish National Fund and The Jewish Colonial Trust. Afflicted with pneumonia, Herzl died in 1904.

Tags: anti-semitism, nationalism, theodor herzl, zionism