Why Things Are Looking Up

Right now, many people on the Right are feeling sort of depressed. This is normal when you consider that modern society is an unnatural, inhuman, ugly, blighted, self-hating, and suicidal path that makes everyone existentially miserable by wasting their time and depriving them of the purpose in life they need, beyond material success, to feel that their lives have meaning.

In other words: every day that you wake up in this society — which is in the middle-to-late stages of failing just like Rome 1.0 was — you are probably going to be depressed because you notice too much. That tendency to notice is what makes you a Rightist, because we pay attention to results in reality instead of feelings and social emotions.

But take heart! We are in the midst of a vast historical shift, and things are getting better by the day, with the potential to actually get good — i.e. non-suicidal — if we keep pushing.

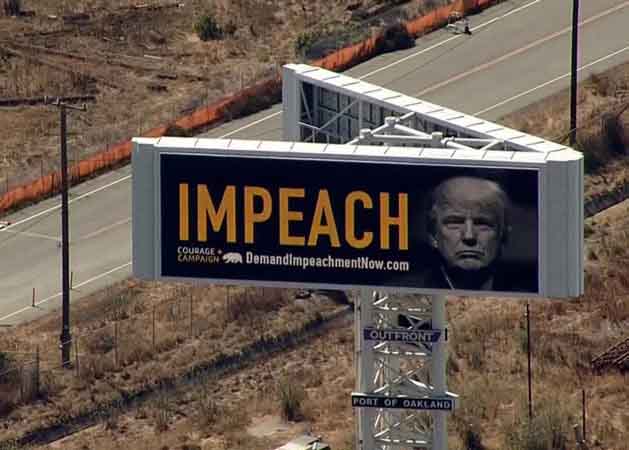

The first good news is that people are adjusting easily to the new. A large group of people who profited under the Obama-Clinton style tax-and-spend neo-socialist system are displeased, but the average person has seen through at least one lie: the sky did not fall, as promised, when Trump took over. Even more, they are adapting to the changes, and see them as the new normal.

After that, we should look at what Trump and Farage have done to play their long game. They have been mild. They have started from small, reasonable expectations such as ending failed policies, and are gradually extrapolating from that. For example, if your government cannot make itself leave the EU, then corruption is the foundation of that government and it should not be trusted.

These “baby steps” have made people comfortable with the changes occurring around them and ready for more. For example, the Trump tax cuts have revitalized the economy in a way that has not been seen since the 1980s; Brexit restored a sense of national direction to the UK that had been missing since the Thatcher years as well. People want more of this positive feedback.

Another piece of good news is that populism is still spreading. With Austria, Hungary, Poland, and Germany all showing impressive gains for the actual Right, populism has taken a foothold not just in America and the UK, but mainland Europe, and it is influencing people there who would like an end to Leftist policies.

Even better, skepticism of certain “holy” institutions — scientists paid to write research papers, journalists who report what are presumably facts, academics who analyze history, government agencies who make recommendations — is rising as each of these institutions proves itself to be capable of being corrupted for ideological purposes.

The biggest changes however are under the hood. We are leaving behind The Age of Ideology, a time when socially-oriented thinking dominated. This thinking, called individualism, insists that the individual is the largest unit of importance in our society, and that individual rights are more important than rights to a shared purpose like civilization.

The Age of Ideology is the age of individualism, or the time in which the human individual was seen as the focus of civilization. Now we know better: civilization has to be the focus of civilization, and because the individual is disadvantaged by a broken civilization, it is our first and foremost goal. Instead of looking at individuals, we look at what we share.

Populism is the first step in this transition. As one expert opines, populism is interpreted democracy without direct democracy:

A populist, Kaltwasser says, is someone who believes that society is split between the pure people and the corrupt elite. The moral judgment is a key part of his definition. Lots of people can agree that society contains both masses and elites, but populists explicitly associate the masses with purity and elites with corruption.

What follows from populists’ belief is that politics should express “the will of the people.†The job of the leader is to channel and express the people’s will. But that can be a slippery slope toward autocracy. In the extreme, anything that blocks the will of the people is seen as a useless or harmful impediment—even courts and legislatures.

…Populism has two opposites. The one everyone thinks of is elitism, which doesn’t have a lot of (open) support. The other, Kaltwasser says, is pluralism. Pluralists believe in democracy but reject the populists’ idea that there is a single “will of the people.â€

Let us translate that: the will of the people is interpreted by a populist leader, who is opposed by elites who are elected or given power by their wealth, and if this will is obstructed, it is fair play to remove impediments like elected representatives, courts, laws, and by inference, democracy itself. This makes more sense than it initially appears to.

First, it finally resolves the delegation versus proxy argument. Some say that we elect the best people that we can and delegate the responsibility for making correct decisions to them; others say that our leaders are our proxies, and we elect them to do specific things. Neither side has been proven right because at times both are.

Populism resolves this paradox: the leader is the one who, eschewing the false elites, figures out what people actually need instead of what they desire, are fascinated by at the moment, say they want, or even vote for. He or she is a translator of dreams, listening to concerns and finding solutions.

This kills utilitarianism, which is the idea that whatever most individuals think is a good idea must be a good idea. That is an extension of the social principle itself which holds that happiness is found when everyone in the group (or as close as possible) is happy. The will of the people, per populism, is something eternal.

And then, finally, we come to the kicker. Populism rejects pluralism, or the idea that people of different backgrounds, radically different viewpoints, and contrasting culture or values can exist in the same society. For there to be a will of the people, there must be a people, and everyone else at least has to be cool with letting them drive.

Populism rejects all that has happened in the West for the past thousand years or so, as we have steadily been drifting from having kings who acted according to eternal tradition to mass culture comprised of many individuals assembled into a mob through the pathology of herd behavior. Populism is the beginning of the reversal of our misfortunes.

The individualism it replaces takes many forms but its essential idea is that of the individual, which is expressed through liberalization more than anything else, which means relaxing the rules which have protected us since time immemorial because individual people want more freedom than the rules provide. From that comes the spectrum of liberal beliefs, which has just become a victim of history:

Liberalism is the modern political philosophy of the emancipated individual, defined in the “state of nature†philosophies of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke as a monistic and desiring self. The condition of the “state of nature†is the condition of absolute liberty: the capacity of the individual to achieve his or her desires without obstacle. But because such a condition gives rise to conflict, government is created to secure the rights of such individuals. Under liberalism the primary reason that we have a public order is to secure individual liberty.

Liberalism is thus a political philosophy that rests upon the realization of the autonomous individual self. This means not only must such individuals be politically free from arbitrary government power, but they must be free from what come to be considered all arbitrary and unchosen relationships that include social and familial bonds. Not only must all relationships ultimately be the result of the free choice of the sovereign individual, but, in order to preserve the autonomy of the liberated self, those relationships must be permanently revisable and easily exited. Thus, liberalism not only shapes our public institutions, but our social and private ones as well, ordering society toward the sovereign choice and autonomy of the individual choosing self. We see the liberal human coming fully into being not only in our political domain, but in the breakdown of most of our social and familial institutions, including the rise of the “nones, “moralistic therapeutic deism,†and the deepening generational avoidance of commitment, marriage and children.

We can say, then, that liberalism is the political operating system of America. Our different parties are like “apps†that operate on that liberal operating system, reflecting its deepest commitments in what are most often its main political agendas: on the Right, the picture of the emancipated individual chooser that animates libertarian economics; and on the Left, the vision of the emancipated individual chooser that animates their libertarian “lifestyle†aspirations, particularly relating to sexuality and abortion.

You may recognize similar language in the above paragraph to what was expressed during The Renaissance and later during The Enlightenment:™ that instead of an order of nature, the human, and the divine, we need an order of the human individual exclusively, as in “man is the measure of all things.” This is individualism expressed as a philosophy.

Liberalism manifests itself in democracy, where the vote of the individual — no matter how little they know — is the same value as any other. We see it in order social order, which emphasizes equality, or in other words not dinging someone in social status for being dumb, evil, or otherwise icky.

We also see it in consumerism, which is the market applied to the idea that every individual knows what they need best and should be subsidized by the welfare state in pursuing that goal, which leads to a “race to the bottom” in terms of quality and venality of products. It also appears in our art, architecture, music, literature, philosophy, and law.

Most people do not understand liberalism because it promises certain abstract things, and delivers something entirely different. This split reveals the difference between values and value instantiations, and explains why people only react after seeing the results of a policy; they cannot extrapolate the latter from the former. As one explanation points out:

This matters because a great deal depends on the concrete examples we use for values. In our research, we refer to the concrete examples as “value instantiations”. People are more likely to exhibit a value in their judgements of a situation and in their behaviour if they have recently been thinking of common, typical concrete examples of a value rather than of rare, but equally valid ones.

Common examples “fit” a particular value more obviously and specifically, and can act as stronger reminders of the value than rare examples. As we have seen, recycling is an easy and obvious fit for protecting the environment, whereas becoming a vegan might be thought of as a more obvious fit for other values, such as health or the treatment of animals. Its role in environmentalism gets blurred.

This kind of blurring comes from a disconnect between the abstract meaning of values and the varied ways in which people apply them. In working to tackle environmental and social problems, we overlook the links between values and value instantiations at our own peril.

In other words, people do not deal well with abstract theory; they require concrete examples. This is why literature is more popular than philosophy, and why visual aids predominate in meetings even among intelligent people. Microsoft PowerPoint is founded on this principle entirely.

With liberalism, we get told some things and not know what they mean, fill in the blanks with the type of conjecture that seems normal. For example, consider these aspects of liberalism:

- Equality. To most of us, equality means that everyone is treated the same way. They are, after all, …equal. But in reality, it means that we must make people equal, because otherwise the philosophy debunks itself. And so, equality means — and never varies from this — taking from the succeeding to give to the less successful.

- Pluralism. People think that pluralism means that every belief system co-exists happily, with each person in their little solipsistic sphere. In reality, pluralism means that society must adjust to fit every belief system, which means that it can have no values in common, so any assertion of the values of your group is viewed as a special privilege by others, which causes them to demand privileges in return. This creates unresolvable internal conflict.

- Democracy. On the surface, democracy sounds like the idea that every vote counts. In reality, it means that only those in the middle of the spectrum count since outliers are eliminated. This means that democracy, on the whole, is the least flexible political system ever created, because it keeps following whatever assumption most of the masses are pursuing.

- Pacifism. In theory, pacifism means eliminating conflict by removing the differences between groups. In reality, it means that whoever has the fewest values wins because they have the least to defend, where anyone who wants to defend their values is seen as violating the commitment to lack of conflict through lack of differences.

The concrete value entirely differs from the abstract values because language is categorical, while concrete examples are procedural. This means that we hear one thing, and then receive another, a fact which cannot help but be taken advantage of by those who wish to manipulate us by trading votes for favors.

Manipulating the human need to be important, these abstract values appeal to our sense of needing to be in control. People feel in power when they are able to make decisions that flatter their own narrative of who they are personally and why they are important, and they quickly become addicted to this mental state.

This attack on the individual — through individualism — proves hard to resist because most people are natural competitors. If offered a field to play on, they charge forward and try to win, oblivious to the fact that by doing so, they are defeating their own interests. This causes them to act out destructive scenarios that nonetheless are personally profitable.

Competition for power causes people to become oriented toward the self-destructive because if they are able to induce others to self-destruct, they gain personal power, even if at the loss of their civilization:

The in-migration was initially hailed as an economic boon; then as a necessary corrective to an aging population; then as a means of spicing up society through “diversityâ€; and finally as a fait accompli, an unstoppable wave wrought by the world’s gathering globalization. Besides, argued the elites, the new arrivals would all become assimilated into the European culture eventually, so what’s the problem?

As British journalist and author Douglas Murray writes, “Promised throughout their lifetimes that the changes were temporary, that the changes were not real, or that the changes did not signify anything, Europeans discovered that in the lifespan of people now alive they would become minorities in their own countries.â€

…Murray explains the motivation of those who engage in such flights of moral dudgeon thus: “Rather than being people responsible for themselves and answerable to those they know, they become the self-appointed representatives of the living and the dead, the bearers of a terrible history as well as the potential redeemers of mankind. From being a nobody one becomes a somebody.â€

In other words, individualism works against us yet another way: people will vociferously approve whatever makes them feel good about their choices and position in life, entirely disregarding whether it is constructive or destructive. European voters have approved mass immigration many times through this method.

The good side of this can be expressed simply as, “But we are more aware of it now,” and the grim truth is that people are awakening from the stupor of individualism. Instead of trying to make themselves look cool, they are more geared toward an organic view in which they can find a place, and withstand the storm caused by the collapse of a century of unrealistic Leftist programs.

We are experiencing a sea change. People no longer trust ideology because they realize that it is merely camouflage for self-interest, a game theory type approach where the individual simultaneously advertises a positive position and asserts a negative one. Not surprisingly, science shows us that egalitarianism is a defensive measure, not a positive ideal:

He argues that these egalitarian structures emerge because nobody wants to get screwed. Individuals in these societies end up roughly equal because everyone is struggling to ensure that nobody gets too much power over him or her. As I’ve discussed in my last book, Just Babies, there’s a sort of invisible-hand egalitarianism at work in these groups. Boehm writes, “Individuals who otherwise would be subordinated are clever enough to form a large and united political coalition. … Because the united subordinates are constantly putting down the more assertive alpha types in their midst, egalitarianism is in effect a bizarre type of political hierarchy: The weak combine forces to actively dominate the strong.â€

In other words, individualists forsake any sense of shared goal, and instead compete on the basis of what they are to receive. This requires them to demand egalitarianism so that no one else gets any more, which leaves them free to negotiate back-alley deals and buddy transactions whereby they receive more.

Humanity games itself. Hilariously, each individual is betting on receiving more than others, which it guarantees by enforcing egalitarianism, which makes others subject to rules while liberating each individual to compete to the degree that they see is necessary. The most materialistic win under such a system.

When we unleash individualism, we create the tragedy of the commons, which occurs when resources are exploited by the competing careerist ambitions of individuals. Although the Left insists that our problem is inequality, more accurately our problem is equality, or too many people able to raid the same thing.

The failure of “inequality” as a reason for our downfall was ably explained by the mouse Utopia experiment, which showed how equality, success as a civilization, and the resulting plenitude are a formula for self-extermination:

At the peak population, most mice spent every living second in the company of hundreds of other mice. They gathered in the main squares, waiting to be fed and occasionally attacking each other. Few females carried pregnancies to term, and the ones that did seemed to simply forget about their babies. They’d move half their litter away from danger and forget the rest. Sometimes they’d drop and abandon a baby while they were carrying it.

The few secluded spaces housed a population Calhoun called, “the beautiful ones.†Generally guarded by one male, the females—and few males—inside the space didn’t breed or fight or do anything but eat and groom and sleep. When the population started declining the beautiful ones were spared from violence and death, but had completely lost touch with social behaviors, including having sex or caring for their young.

Politically, democracy is the mouse Utopia of opinions: no one is accountable, but everyone has an interest in taking whatever they can, so the system is fully exploited without anyone really knowing why. Individualism of all sorts ends up this way because it is uncoordinated taking of resources, separated from an inherent sense of purpose that would allow collaboration/cooperation.

That kind of setup can fool us for a long time. In the case of Western Civilization, it has been centuries, and the French Revolution which formalized this movement was not long ago. But since that time, despite our increases in technology and wealth which continued from the age before, everything else has gone wrong, and individualism is to blame.

No one in media will come out and say it but the age of individualism has ended, and a new age has dawned based on the ability to work together toward a goal. While things seem bleak right now in the transition, in the long term everything is looking quite wonderful, as we leave behind an era of illusion and find ourselves again instead.

Tags: democracy, donald j. trump, individualism, nigel farage, the age of ideology