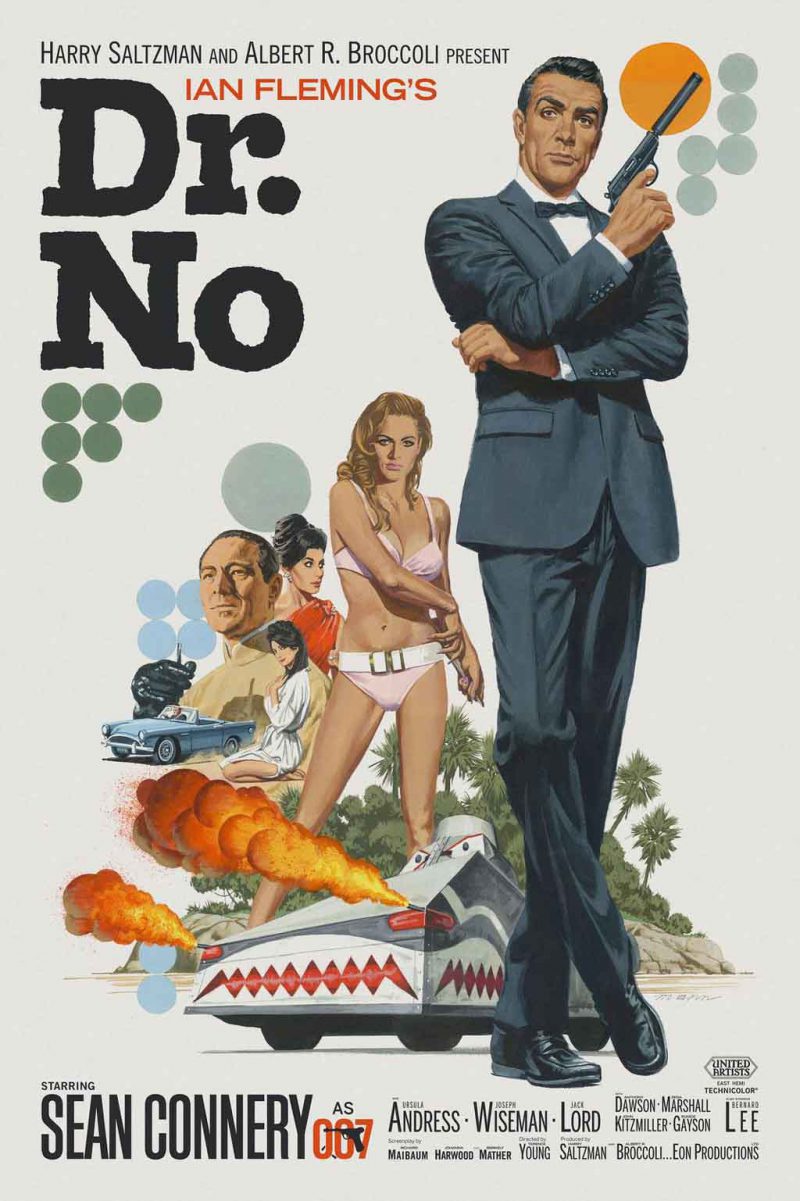

Dr. No (1962)

James Bond burst onto the scene with the most ambitious film in this series. It follows more of the Shakespearean model of older British cinema, focusing on long sequences of activity that culminate in emotionally significant moments. This makes it atmospheric but filled with action without much chatter.

Sean Connery makes his debut as 007, the spy with the “license to kill,” who in his hands becomes a complex character: robotic in his pursuit of his task, creative in finding macgyver-style solutions to seemingly insoluble problems, a consummate actor who adapts to any environment, and caught forever between a wistful melancholy and a barely submerged rage. Connery gives us a Bond who seems like he is on the edge of cracking up except that he has a sense of purpose, making him the comic book hero with depth that Batman, Superman, et al. were incapable of having.

Unlike later Bond films, the gadgetry is kept to a minimum and the plot unfolds systematically but with careful pacing, keeping the first half of the movie as mystery before unleashing the pursuit and challenge narrative that happens when Bond makes contact with the enemy.

For those who want more insight into Bond, a famous scene in this movie involves Bond lying in wait for his prey, pumping him for information, and then killing him. Many wonder if the killing was necessary, or if as facial expressions indicate, Bond enjoys it and then enters into a moment of dark sadness. From the original books, Bond enjoyed dealing justice but was not particularly a fan of killing; he was simply inert to it, because in his view, there were good guys and bad guys, and you shot the latter to save the former. This absolute equation rules Bond in the first movie, where to him, all things are a means to the end of his mission and can be destroyed without guilt.

Ursula Andress serves up a character who manages to be enticing only because she is unaware of herself and in her innocence, untouched by the world of corruption around her. Playing across from Connery, she becomes a shy and brilliant child, baffled by the motivations of others but quick to recognize their lack of place in her world.

One cannot discuss much of the plots of this film because it starts with a few clues and rapidly becomes an engrossing task, which as usual features the end of the world at the hands of SPECTRE, the worldwide criminal organization which is the preferred villain in the classic Bond films.

Aspiring screenwriters might note the tight dialogue and scene transition here. Every scene is part of a quest, and nothing is wasted on the scene other than is relevant to that storyline, which allows for some longer meaty conversation scenes and other short, punchy action scenes with a great deal of variation between. This makes time, place, and people secondary to the unraveling mystery, which drives the movie forward from a sense of inner purpose unlike most action films, where characters venture between locations like changing rooms and then fight the monsters they find there with no sense of overall structure to the narrative.

Diehard Bond fans return to this movie because although made in the early 1960s, it demonstrate careful taste and adept filmmaking, since nothing is out of place or garish, and it stays equal parts threatening and inspiring. Had they made a dozen more of these, Eon Productions would have been the biggest movie house on Earth.

Tags: cinema, film, james bond, movie, spectre