Monkeys With Razors

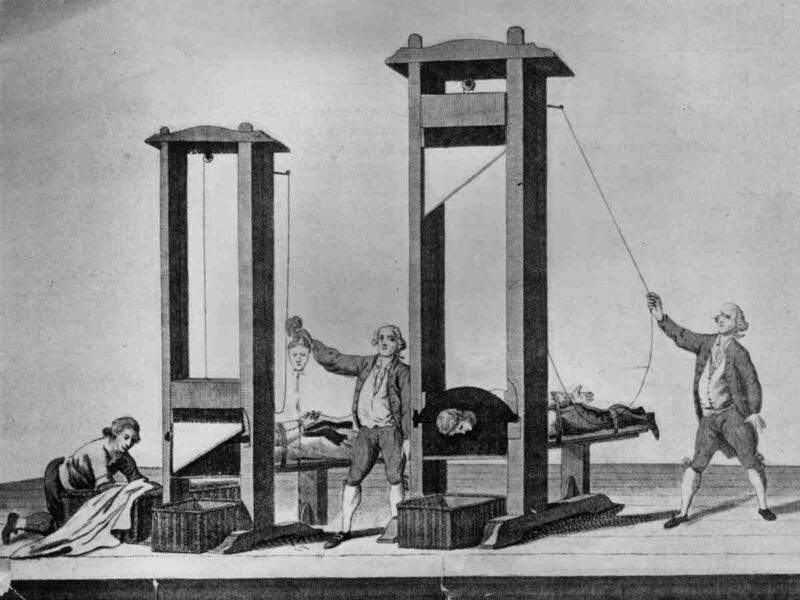

More dangerous than a monkey is a monkey with a razor. In the human case, this razor may be power itself—or the illusion of power. Power can take many forms, for it is nourished by multiple sources, but even when ostensibly rooted in knowledge and intelligence, it may manifest not as wisdom but as arrogance, a hubristic hypertrophy of reason. Nietzsche already warned that the “will to truth” can degenerate into a pathology when it becomes an idol that devours life itself (Nietzsche, 1882/1974). In this sense, rationality without measure easily becomes another form of barbarism—civilized in its attire, but barbaric in its effects.

Paul Feyerabend, in his heterodox interventions, dismantled the aura of science as the final tribunal of truth. In Against Method: Outline of an Anarchist Theory of Knowledge (1993), Feyerabend questioned many of the sacred assumptions surrounding the status of science—particularly Western science—arguing for a more versatile, less orthodox approach to knowledge, breaking through the desiccated boundaries of the scientific method: anything goes, opening the door to other, less regimented forms of knowledge. Later, in Farewell to Reason (1987), he went further, defending even those sources of knowledge long dismissed by the West as irrational or “primitive.” His reminder that Enlightenment institutions quickly generated a new immaturity—where the verdicts of scientists are revered as once were those of bishops—echoes the Nietzschean suspicion that every apparent emancipation risks creating new chains. He writes:

According to Kant, enlightenment comes when people outgrow an immaturity they themselves have inflicted. The eighteenth-century Enlightenment made people more mature vis-à-vis the churches. An essential instrument for achieving this maturity was greater knowledge of man and the world. But the institutions that created and expanded the necessary knowledge very soon produced a new kind of immaturity. Today the verdicts of scientists or other experts are accepted with the same reverence once reserved for bishops and cardinals, and philosophers, instead of criticizing this process, try to demonstrate its internal ‘rationality.1

True though this may be, it is also a razor in the hands of a monkey.

Questioning, to be sure, is a positive and creative act—yet only if the one who questions is equipped to do so. The democratization of information, so often celebrated, tends to flatten the terrain of knowledge. By “leveling the playing field,” it reduces the distinction between expertise and ignorance, as if knowledge itself could be distributed equally like coins at a marketplace. But knowledge resists Equality; it is intrinsically hierarchical. The self-perception of wisdom by the unwise, what modern psychology calls the Dunning–Kruger effect (Kruger and Dunning, 1999), produces not enlightenment but its parody: a false awakening that confuses ignorance with lucidity. More precisely, the democratization of the self-perception of wisdom—leads inevitably to that assault upon Mount Stupid so vividly.

Here Sloterdijk’s analysis is illuminating: the contemporary subject often dwells in what he calls kynical reason, a corrosive, self-satisfied critique that masks impotence (Sloterdijk, 1983/1987). This pseudo-radical questioning—typical of conspiracy theorists and self-styled iconoclasts—resembles the immaturity Feyerabend described, but with an additional twist: it cloaks itself as superior maturity. The monkey, now clutching the razor of critique, lacerating not structures of domination but the very tissue of shared rationality.

There are, quite simply, individuals who are not prepared to question. To interrogate reality from a base of ignorance is not a triumph of reason but its caricature, a regression into the pre-critical.

It is precisely here that the line must be drawn against the monkeys with razors—or, at the very least, that they be left as mere monkeys.

Notes.

- The oft-cited passage concerning Kant, Enlightenment, and the new “immaturity” produced by scientific institutions does not in fact belong to the main body of Farewell to Reason, but rather appears in a footnote in the English edition. Specifically, it comes from Feyerabend’s response to the essays collected by H. P. Dürr in Versuchungen (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1981). The English edition of Farewell to Reason incorporated this material in a modified form, adding footnotes that differ from the original German version. As a result, the English reader encounters a formulation—comparing the reverence for scientists and experts to the former reverence for bishops and cardinals—that does not occur in the same wording in the German text. The discrepancy illustrates Feyerabend’s own practice of rewriting and expanding his arguments for different audiences, often treating translations not as literal reproductions but as occasions for variation and supplementation.

References

Dürr, H. P. (Ed.). (1981). Versuchungen: Aufsätze zu Paul Feyerabend. Suhrkamp.

Feyerabend, P. (1987). Farewell to reason (Rev. ed.). Verso.

Feyerabend, P. (1993). Against method: Outline of an anarchist theory of knowledge (3rd ed.). Verso.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

Nietzsche, F. (1974). The gay science (W. Kaufmann, Trans.; 2nd ed.). Vintage. (Original work published 1882)

Sloterdijk, P. (1987). Critique of cynical reason (M. Eldred, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press. (Original work published 1983)