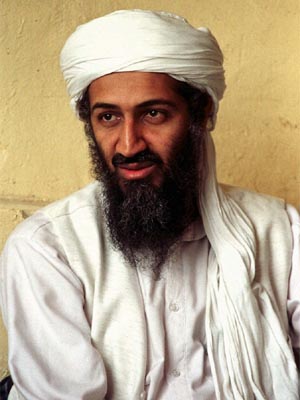

Osama bin Laden

The killing of Osama bin Laden is a classic example of a symbol that masks a more complex reality.

The killing of Osama bin Laden is a classic example of a symbol that masks a more complex reality.

We often wish that we could hold the world in the palm of our hands, whether metaphorically or literally. If we could distill all that complexity to a single thing we must approve or reject, life would be so much simpler.

One way we do this is to stop considering broader implications, and consider only the impact of something on us in terms of impeding our will. If it helped us or didn’t interfere, it’s Good. If not, we declare it Bad and try to invent some abstract ideal that will prove it so.

However, at the end of the day, those types of decision involve treating reality like a symbol and ignoring its broader implications. As a result, they produce problems:

- No legitimacy. Whatever we think of the outcome, the Nuremberg Trials provided a sense of legitimacy because they were consistent. When you go to war for peace, democracy, justice and other big broad symbols, you should try to demonstrate those. The Osama raid was not a capture raid; instructions were issued in advance to kill all men encountered. That’s an assassination.

As another source put it:

But capturing and trying violent leaders is probably a better marker of the end of such organizations – the chances of such an outcome being higher when such leaders recant their views and call on their followers to lay down their arms. Abimael Guzmán, the leader of the Maoist Shining Path in Peru, and Abdullah Ocalan, the leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in Turkey, are notable examples of this.

By contrast, far from causing the demise of an armed movement, the killing of a charismatic leader at the hands of his enemies can transform such a figure into a martyr. Che Guevera was far more valuable to leftist militancy after his death than he was while alive. – Project Syndicate

- Not structural. George W. Bush, as president, attacked the support structure for al-Qaeda: Islamic republics that adopted the Islamic extremist hierarchy into their propaganda or government. In particular, he tamed the Saudis with diplomacy and destroyed Iraq, which so far had supported the most radical terrorism because it was in a position to conduct weapons from the Russians into the hands of Islamic extremists. Osama bin Laden did not have such pull.

- Martyrdom. After eight years of American action against him, Osama bin Laden was boxed into a corner. His attempts at terrorism in the USA and Europe failed more often than not, and he had no visible support from governments, making his organization appealing only to the already alienated outsiders. This hurt his recruiting and thinned his staff. Even more, he looked impotent and soon to be forgotten; toward the end of the Bush presidency, for a time he was. Killing him affirms his importance.

- Legitimizing terrorism. Eye for an eye is a great policy except that it legitimizes the original deed. If he kills some of ours, and we kill him, we’re in effect saying that a war of attrition has been joined. A future terrorist needs only look back to this incident, like our domestic terrorists looked to Ruby Ridge and Waco, to see legitimacy in his cause.

- Lazy Clinton-years policy. Clinton would have done the same thing. Where a Republican president will commit boots on the ground to destroy the infrastructure, Democratic presidents tend to make symbolic moves that allow the infrastructure to thrive. Now that our fake war is over with the death of bin Laden, we will (if history serves) relax our pressure on the money-hoarding, weapon-gathering and extremist-associating practices that happen before any organization is ready to make open war, even terrorism.

- Romanticizing. The story is now that Osama bin Laden resisted the West all his life and was killed unarmed by a bunch of highly-trained assassins with a trillion-dollar military arm behind them. No one can survive that. We could have had another story, one of Osama dying in obscurity after drifting toward more abstract philosophies, as some evidence suggests was happening.

In Europe, there has been criticism of America that should for the most part immediately be forgotten. Everyone resents a superpower, and so most of the world is critical of America most of the time, which causes their criticisms to become a sort of background noise. There’s one legitimate point here however:

Many in Europe have questioned not only the manner of the killing of an unarmed man, but also the taste and dignity of the American public who chanted ‘USA’ in the streets.

Expressing these sentiments is Britain’s Archbishop of Canterbury who said: ‘I think the killing of an unarmed man is always going to leave a very uncomfortable feeling because it doesn’t look as if justice is seen to be done.’ – The Daily Mail

The addled Euro-pundits can’t quite put their finger on it, but the killing of Osama bin Laden as a political symbol rings hollow. It’s a crass call to round up the troops and put on a good face while more serious problems lurk.

No war is started by one man, or perpetuated by him.

The conflict between radical Islam and modern liberal democracy is bigger than America. This is elements within the Middle East making war on their nation-state governments because those governments do not accept the mandate of fundamentalist Islam; this parallels the war between social conservatives in America, who want a society based around healthy values, and the liberal modernists who don’t think values except for political values are important.

In many ways, killing Osama bin Laden is our way of silencing this dissent in ourselves.

For example, it’s one thing to say that all speech should be tolerated and anyone should be able to do whatever they want to do. That’s a negative reaction to intolerance and authority abuse. But what kind of society do we actually desire?

It is my hypothesis that the fundamental source of conflict in this new world will not be primarily ideological or primarily economic. The great divisions among humankind and the dominating source of conflict will be cultural. Nation states will remain the most powerful actors in world affairs, but the principal conflicts of global politics will occur between nations and groups of different civilizations. The clash of civilizations will be the battle lines of the future.

[…]

What do we mean when we talk of a civilization? A civilization is a cultural entity. Villages, regions, ethnic groups, nationalities, religious groups, all have distinct cultures at different levels of cultural heterogeneity. The culture of a village in southern Italy may be different from that of a village in northern Italy, but both will share in a common Italian culture that distinguishes them from German villages. European communities, in turn, will share cultural features that distinguish them from Arab or Chinese communities. Arabs, Chinese and Westerners, however, are not part of any broader cultural entity. They constitute civilizations. A civilization is thus the highest cultural grouping of people and the broadest level of cultural identity people have short of that which distinguishes humans from other species. It is defined both by common objective elements, such as language, history, religion, customs, institutions, and by the subjective self-identification of people. People have levels of identity: a resident of Rome may define himself with varying degrees of intensity as a Roman, an Italian, a Catholic, a Christian, a European, a Westerner. The civilization to which he belongs is the broadest level of identification with which he intensely identifies. People can and do redefine their identities and, as a result, the composition and boundaries of civilizations change.

[…]

Third, the processes of economic modernization and social change throughout the world are separating people from longstanding local identities. They also weaken the nation state as a source of identity. In much of the world religion has moved in to fill this gap, often in the form of movements that are labeled “fundamentalist.” Such movements are found in Western Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism and Hinduism, as well as in Islam. In most countries and most religions the people active in fundamentalist movements are young, college-educated, middle-class technicians, professionals and business persons. The “unsecularization of the world,” George Weigel has remarked, “is one of the dominant social factors of life in the late twentieth century.” The revival of religion, “la revanche de Dieu,” as Gilles Kepel labeled it, provides a basis for identity and commitment that transcends national boundaries and unites civilizations. – Samuel Huntington, “The Clash of Civilizations”

There is no consideration of the consequences of “everybody do whatever you want, every man for himself, just keep going to work and buying stuff” as an ethos to a civilization, yet the intersection of democracy and liberalism seems to produce it every time. In fact, loosening the rules just ensures that commercial interests have a greater sway, and they want culture and religion out of the way.

Even in the United States, we can see that whether Osama bin Laden went about his political agenda the wrong way — by being a murdering terrorist — that his viewpoint, if taken in the abstract, might apply to us. Do we want a family-oriented society that believes in a morality higher than the individual? Or do we want an anarchistic open-air bazaar with no standards, in which things inevitably degenerate to the lowest common denominator?

When we killed Osama bin Laden, we wished we could have killed this conflict. Life would be so much simpler! This conflict underlies our culture wars, our political division, our recurring Civil War, and even our social division between urban and suburban values. It’s so much bigger than one man.

Yet like fanatics burning books, we destroy the symbol and hope it (magically) makes the deeper underlying problem go away.